THE FIGURE IN TRANSLATION

Nader Tehrani, published in Digital Fabrication in Interior Design, edited by Jonathon Anderson and Lois Weinthall

The Identification of the Figure

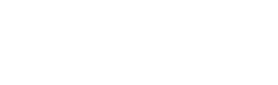

At first glance, the body, the object, and the enclosure would appear as a menagerie of three random things, but what I will attempt to draw out of them is a common investment in the art of figuration. Behind this investment lies a discourse on the nature of representation and how reality is depicted from within a medium: that is to say, that our perception of reality emerges from the particularities of a medium, but also that when a shift in medium occurs, there is also a change in techniques, methods and the need for translation. The histories behind the quest for the ‘real’ are laid out in traditional art history courses; the evolution of the body in Egyptian sculptures, and their requisite transformations in the Greek kouros, from the archaic frontal pose to the eventual contrapposto position marks a passage of technical and intellectual cognition. Embedded in this historic arc is a narrative of the human’s pedagogical vicissitudes – albeit over centuries – learning eye-to-hand coordination on the one hand and establishing a conceptual dialogue with the real on the other. With the human figure under observation, this involved the invocation of an idea about optics and ‘how’ to see, centering the eye itself as a subject of art – with an ability to transpose one three-dimensional reality onto another. The inexactitude of that translation has been prone to significant debate throughout history also, with the idea that verisimilitude is subject to a range of possible interpretations, from the abstract to the hyperreal. Also embedded in this history is the idea that the body, as subject, is prone to two very different forms of registration: The first as a pictorial icon, whose recognizable parts speak to the narrative of the whole; and the second as an index, whereby traces and imprints of the body may be present without any visual resemblance to the body itself. Whereas the former relies on optics and visuality as the center of artistic production, the latter recenters cognition through conceptual avatars that register the production of knowledge through other means and senses.

The Body in Architecture: The Ergonomic Index and the Projected Figure

By way of translation, the presence of the body in architecture is registered in both explicit and implicit ways. On the one hand, within the doctrine of humanism, there is a history of Western architecture whose treatises are centered on the human. This is as much evident in the sketches of Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian man as in Le Corbusier’s ‘Modulor’; notwithstanding the ideological sway this narrative has offered the history of architecture, it is poignant in its identification of dimension, scale, and ergonomics as the basis of architectural measure. In it, we have also witnessed the lacuna of other subjectivities whose bodies are absent, be they the result of gender, species, or other living ecologies. Still, if an alien were to discover the remains of the planet Earth in some future history when humans no longer roam, they might still discover the registration of an inexact body that is a subject of architecture itself. How that registration occurs is worthy of closer inspection.

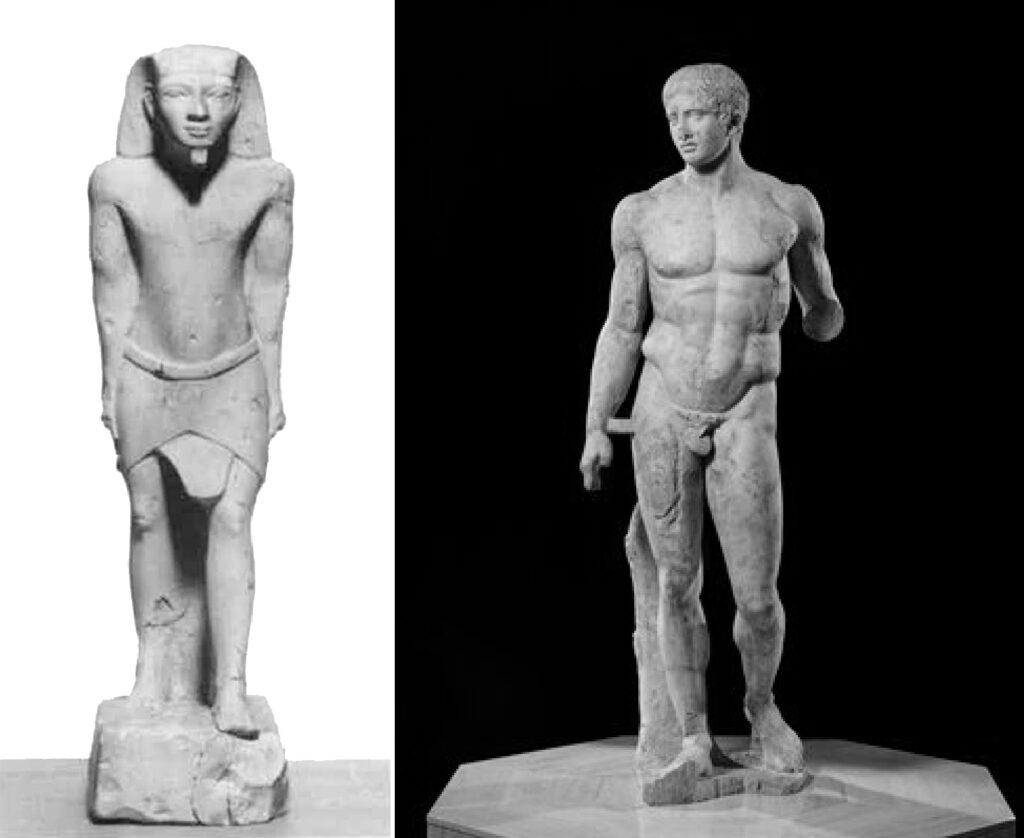

The morphological particularities of the body offer a productive clue via its engagement with architecture, if only that the interface between the human and its environment may begin with the body as a system of parts: the torso, limbs, digits, or head all establish a special relationship with the built environment. With the hand as maybe one of the most dexterous instruments of intelligence, it is also the most prone to architectural engagement, not only in the tactility of surfaces around us, but in the mechanical protocols of hardware, instruments and vessels that mediate between the human and its environment: doorknobs, pulls, flatware, cups and many industrial design artifacts are the first registration of such encounters.

The Num Num Flatware (above) draws from a history of silverware products whose impression of the figure is the result of a latent tension between the material technologies at work in the production of metal and the mechanics of the hand as it navigates the world around us. With two dominant modes of production, metalworks have been defined by a ‘stamping’ of sheet metal on the one hand, and the casting of liquid metal on the other – obviously involving two very different requisite figurative opportunities. In the Num Num Flatware, we took advantage of casting protocols, not only to exacerbate the figural properties of the utensils, but to radicalize their ergonomic potential in confrontation with the hand. If the traditional stamped flatware is balanced out like a dumbbell, with an hourglass figure around which the hand can conform, the Num Num series establishes a hand-to-glove relationship between fingers and utensils, creating a center of gravity within the central mass of the flatware, and triangulating its facets so that three digits may hold it with ergonomic facility: The figure of the utensil becomes an index of the hand. Similarly, the Nob Nob Doornobs series (below) offers a research matrix of relationships between the body and hardware, some of which are related to conventional canons, while others are related to novel ways of engaging the body. If the lever and round knob types emerge from well-established historical models, they create a generic rapport with the body, biasing either mechanical or geometric performance. However, some of the more speculative renditions of knobs in our matrix escape the platonic bias of generic versions in search of manual morphological twists whose mechanical and ergonomic performance come into dialogue. In both instances, the Num Num and Nob Nob series conceal the image of the hand itself, if only to reveal it as an index, imprinting its performance on the body of the hardware itself.

As we scale up to the architectural framing of installations and furnishings, the presence of material aggregation impacts its relationship to the body, in part becoming an even more important protagonist in the embodiment of form. Consider the stacking of plywood as a tectonic idea, translating butcher block technology into more contemporary terms, and how this may be interpreted through three projects.

The Vero Dresser and the Laszlo Files are both milled projects, whose excavation of plywood offers a space of intervention for finger pulls. The Vero Dresser is premised on a simple principle of horizontal stacking in combination with a hierarchical stacking of drawers whose dimensions vary in ascending order, allowing for programming of different-sized artifacts. The monolithic tendency of this tectonic is amplified by the masonry logic, whereby the drawers are composed as masses of solid ply, without indication of the very void that activates its programming. The challenge, then, was how to create pulls for these drawers while maintaining fidelity to their tectonic logic: The discrete sinuous carving that veers in and out of the outer surface of this mass accomplishes this precise feat. Instead of adding metal pulls, as convention might mandate, we adopted the ethic of a mono-material strategy, forcing distortions in the stacked ply to enable pulls from within the logic of its morphology; the finger engages geometry practically, but the geometry does not emulate the body per se, instead, it invites the body into its logic. In contrast, the Laszlo Files rotate stacked plywood vertically, if only to take the opportunity to mill into the depth of a generic surface. This allows for the projection of an external figure, unrelated to the body entirely, to impress itself on the surface. The routing of multiple layers of ply allows each laminate to gain a voice, such that in their repetition, they can produce a pattern whose affinity with textile can be amplified by the organic logic of the milled surface. Not unselfconsciously, the lightness of the animate figure of undulating fabric is meant to offset the weight and depth of stacked monolithic ply technology. In this instance, the drawer pulls are smuggled into the ‘textile’ surface by way of a shear, a tear in the surface within which the fingers can intervene. Here the human figure, and the figure of a liquid veil come into conversation, both alien to the innate materiality of the plywood itself – but also distinct from each other in both figurative and performative terms.

The projection of external figures and forces onto architecture is nothing new of course. The petrified aqueous surge of Ledoux’s Saltworks in Chaux is a reminder that even the most tectonically integral of details such as the triglyphs of the Acropolis are but mere figurative projections onto the body of architecture. However, the narrative they produce is a critical part of what we inherit in tectonic thinking: effectively, that the expression of architecture is always in tension with the performance of its structural, material and constructive parts. If this is seen as a liability, then I will argue that this is precisely the power of figuration in the arts, whereby the simultaneous presence of semantic and performative attributes contributes to a complex narrative not reducible to the pure claims of a moral high ground. Still, what is maybe most important about the Laszlo Files is that the clad figure and the body’s digits are being interpreted as two different entities, where the first can be seen as an external projection onto the architectural artifact, and the latter is seen as a projection of its metrics, as constraints, onto the body of architecture itself. The Gwangju Biennale Cube presents such a hybrid, whereby the position of the body in variable states of repose are called on to create a liquid surface, whose geometry evades precise semantic claims and only establishes momentary conditions of ergonomic comfort in an otherwise continuous surface. The continuous surface masks what is hybrid accumulation of furniture types, here fused together as chaise longue, bench, chair, among other such categories; by concealing the seams between each object type, we are able to reconcile them into an organic whole, erasing typological and semantic differences entirely. In turn, the use of a singular material allows them to be brought into unison, both symbolically, and ergonomically.

The Figurative Object: The Means and Methods behind Architectural Protocols

While traditional interpretations of architecture conventionally revolve around the scale of building, landscape, and urbanism, the architectural invariably somehow insinuates itself onto the ‘object’ – be that the object of sculpture, installation, furniture, or even more intimately aligned with the body, that of clothing. What is of importance in this change of scale is not always the size of the artifact itself, but an understanding of the discrete forms of production that lie behind the fabrication of these realms, what is referred to as the means and methods of construction in architecture. Insofar as the design discipline is invested in its design intent, I would argue that if the discipline wishes to lay a claim on the integrity of its deployment, then it must also produce a process that guarantees a precise mode of fabrication that is aligned with its intent. In part, this requires of the architect a deeper understanding of materials, their methods of assembly, the trades that produce varied systems, and the actual labor involved – the sum total which comprises of the means and methods.

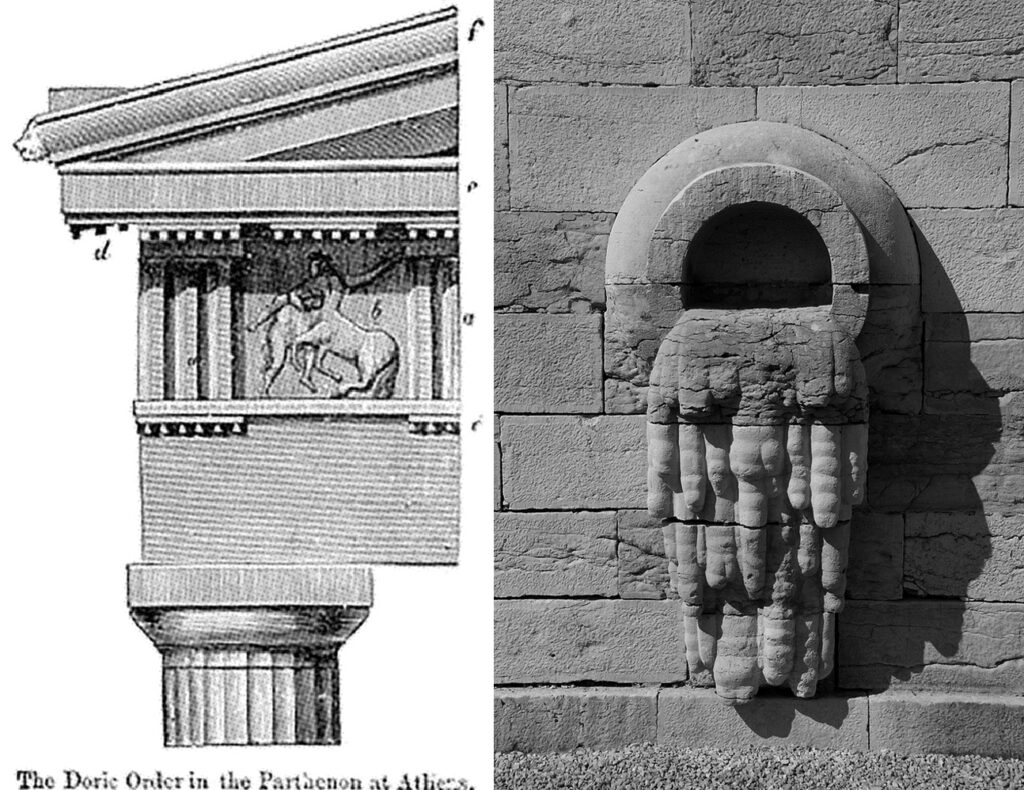

While it is assumed that the means and methods of architecture emerge from within the discipline – in the arena of casting, welding, millwork, and other such trades – some of the more speculative forays into inventive terrain emerge from the transposition of one discipline onto another. In the context of the installations at MOMA and Harvard’s GSD – Fabrications (above) and Immaterial/Ultra-material (below) respectively – techniques of the sartorial were adopted to find ways of creating a meaningful relationship between that which clothes the body with that which clads a building. Insofar as clothing is possibly the most intimate scale of architecture, sheltering the body as it were, its confrontation with fabrics, and its requisite methods of pleating and darting suggest innovative ways of translating its thinking to the architectural scale.

For the Fabrications project, we had the opportunity to work with steel in non-standard ways in the early days of digital fabrication; in trying to evade predictable assemblies composed of stock extrusions such as I-beams, angles and channels, we proposed a folded structure whose origami-like composition could offer it structural stability through its own geometries. Given the limitations of sheet steel dimensions, this also meant that we needed to subdivide the installation such that the continuity that is intuited in its reading is actually fabricated out of discretized parts. As such, the subdivisions were concealed within the stringers of the folded plates, and in turn those very stringers served as the jigs to ensure tight tolerance for the folded plates wrapped around them. Most importantly, the folds were enabled by an offset laser-cut incision within the steel that allowed for a meticulous pleating pattern. If the body serves as a template for clothing, here the concealed jig serves as the installation’s measure, and in turn, if the pleat helps to contour the body, the steel pleat allows for structural rigidity in the installation. For the Material/Immaterial installation, a similar subdivision of panels was needed – this time because of the compound nature of the curvatures we had conceived. The curvatures corresponded to three conceptual segments of the site: the guard station, the threshold and the column wrap. For a single surface to navigate this complex geometric terrain, we strategically elected to conceive it through a developable surface, hence adopting darting to create conical derivations of the ruled surface. Interestingly, the combination of wood laminate and the darting process produced its own dynamic of strengths and weaknesses, depending on the grain of the wood, and the orientation of the darts. Here, the figurative is invoked not only in the body’s connection to the sartorial techniques that facilitate the installation’s conception, but also in reference to the organic body of the installation itself composed of a continuity of smoothed tessellation.

The Architectural Enclosure: The Reciprocities of Spatial and Formal Figures

As the scale of design increases, so too does the complexity of parts that constitute the fabrication process. The building’s tectonic systems, differences between interior and exterior finishes, varied performance criteria and basic conventions begin to insinuate themselves on the body of a built enclosure. To this end, it is also often increasingly difficult to maintain the level of fidelity to figurative strategies as they tend to get compromised by the very conventional systems that get imposed onto them, fragmenting the singularity that a figure requires. To the degree that part-to-whole relationships matter in the conception of a figure, this also brings up interesting representational predicaments at the heart of this essay: namely, to what degree is architecture bound to communicate its content on the form of its body, what of the interior gets represented on its skin, and how do the organs of a building’s systems become registered in the morphology of the envelope? Even if history has already grappled with such questions, it remains a conceptual weight on the discipline today.

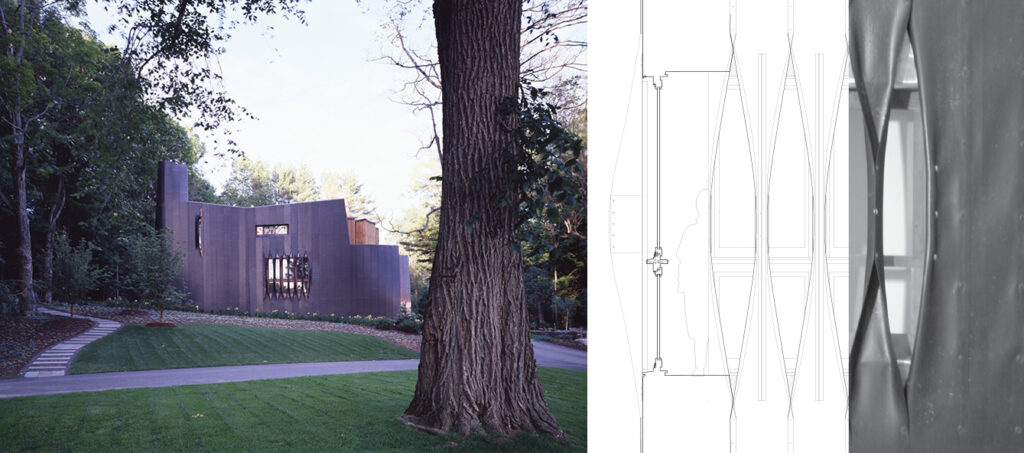

In the context of the Rural House (above), we were able to sustain such a fidelity, in great part because of the disciplined transposition of a roofing system onto a rain-screen façade. Adopting a striated rubber membrane system, we were able to run continuous ribbons of membrane over the ledge of the roof, allowing the water to drain down the elevation unfettered. As an extension of the sartorial exercises, this experiment leveraged the malleability of rubber as a plastic medium to mold around organic metal stirrups, whose function was to maximize the views through what are otherwise conventional windows looking out from the interior. Here, the agency of materiality defines the figurative potentials of the building’s body, and in turn its language. At the same time, it is primarily a skin, shrink-wrapping a contained program, composed of a living room with a fireplace and entry portal at the two extremes of the façade, both of which give more figural latitude to establish formal and spatial reciprocities between the program and its expression.

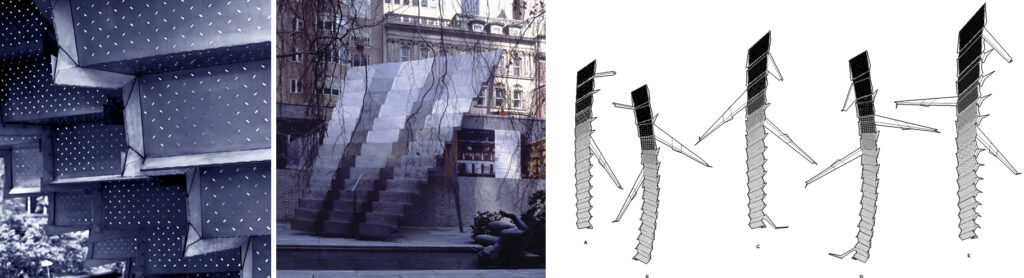

In thinking closely about the relationship between the body, the object and the enclosure, our research on the stair as an object-type revealed to us a certain conceptual consistency that helps to advance this argument. This is explored in the Rural House, the Tongxian Gatehouse (above), the New Hampshire House (below), and Villa Varoise, as they all share a common trope: They adopt the anomalous spatial and sectional condition of the stairwell to sculpt and enclose the space as a legible figure. In doing so, they imbue a particular agency to the stair as an instigator of both spatial and symbolic form. To begin with, they are all observant of a salient spatial quality that only a stair can produce: Its diagonal organization produces a residue of space both beneath the stair, as well as above, where headroom is required. To the extent that architecture is not driven by necessity alone, the figurative impulse frames the peculiarity of this space for the exploration of morphological invention, and in turn, finds ways in which the stair is able to be indexed onto the enclosure of the building. In observing the condition of the residue in the Rural House, the stair and corridor are planimetrically overlapped to share the same zone, and in doing so, effectively configure the stair in the space of the envelope, telegraphing its enclosure onto the exterior of the building, however allusively. In the Tongxian Gatehouse, a similar sharing of stair and corridor zone collapses the circulatory sequence into a figure-eight pattern; while the body’s motion is indexed in the enclosing faces of the interior, it also reveals itself at the destination atop the building, where the envelope molds itself around the architectural promenade.

In the New Hampshire House, the elliptical morphology of the courtyard house is culminated by a stair, whose ascent to the roof offers unmitigated panoramic views onto the Presidential Range. The underbelly of the stair takes advantage of two architectural opportunities: First, to use the residual space to create a monumental portal into the house; and second, to translate a New England vernacular cladding system (the vertical tongue-and-groove) into a contemporary configuration whereby the main enclosure of the façade is called on to migrate from wall to ceiling by way of the ruled surface. Here, the body of the stair establishes the metrics of the stair–riser relationship, while the dimensions of the wood siding defines the parameters of the ruled surface. Metaphorically, the reciprocity they offer is less hand-to-glove and maybe more hand-to-mitten, allowing for a loose fit that is yet attendant to the problem of formal registration between the interior organs and the exterior expression. Finally, in Villa Varoise (below), another rendition of the same stair is adopted as a hinge on two corners of the house, conjoining the upper and lower plans into a continuous donut. Similar to the New Hampshire house, the staircase on the northeast corner of the house forms a critical juncture of arrival: It mediates the sloped topography of the site by lifting the upper level over the lower, and using the stair itself as a structural pylon for the upper wing of the house whose main façade serves as a beam cantilevering over the continuous landscape below. Here, the envelope is no longer conceived as a shrink-wrapped condition, but rather as the raw matter of architecture: The structure is the envelope itself. In turn, the grained registration of board-forming for the formwork serves as an index of the structural geometry at work in the building. In all cases, these stairs do not serve mere circulatory functional purposes; rather, they emerge as protagonists, offering a trigger for creating a critical link between the body in motion, the object to be specified and the enclosure to be formed.

The Digital Figure

In closing, I return to the main prompt of the book and its challenge to bring the body, the object and the enclosure into critical conversation. While I have deliberately not yet focused on the digital, it must be underlined that the historical project behind figuration precedes contemporary technologies. As such, it underscores the way in which the arts can be motivated through two modalities: on the one hand, through the longue durée and a conversation with history; and on the other, through the instrumentality of a particular medium whose techniques prompt us to think differently because of the way they allow for different forms of intellection. In part, the work presented here attempts to bridge this false dichotomy by bringing long-standing debates into conversation with emerging means and methods of production, but also in looking closely at the protocols of production today to see how they might redirect historical thinking altogether.

If the quest for the real in sculpture adopted nature as its foundation, it is because it had the human figure as a model from which to probe questions of representation. In architecture, I would argue there is no ‘natural’ foundation: The architectural discipline emerges from a discursive moment where acts of design and building slowly evolve into a state of self-consciousness, demonstrating the artifice of representation itself. The ‘real’ of architecture is registered in the contingencies of the discipline, and how they impose themselves onto the discourse. In the context of this article, I have only referred to a few conceptual terms: the presence of type, material agency, the structure as catalyst, the architectural promenade, the relationship of form to content, among other things, none of which emerge from nature as such.

Accordingly, in confronting these discursive disciplines, much of architectural pedagogy has evolved around the principle of visual literacy, effectively connecting ideas with techniques to create form, space and material; in turn, to the degree that forms, spaces and material have the capacity to mobilize ideas through their own agency, pedagogical models revolve around critical methods to bring them into discourse. At the same time, it must be underlined that the discipline has thrived for several hundred years almost single-handedly with a bias toward optics, composition and how architecture is formed through visual means. In effect, the means and methods of its representations have been visual whether drawing by charcoal, pencil or even the digital mouse in the context of software such as Rhino. The more interesting and critical transition that has occurred since revolves around the advent of computation, artificial intelligence, and the interface between the virtual and the physical, in great part because many of the initial protocols they are founded on are rooted in non-visual means – scripts and algorithms – such that the architect’s traditional command over composition becomes secondary to the ability to navigate codes. More interestingly, it is the confrontation of the computational and the physical (the non-visual and the compositional) where the agency of this age comes to fruition. The figurative results of code are no less seductive, or meaningful, than that of the composed image; however, they do not rely on the authority of precedence, nor a visual model, but rather rule-based constraints whose parameters may become the source of both play and discipline. If that discipline is non-visual in the first instance, its impact on the figure is no less radical in the second.

The digital problematizes the project of representation in that it displaces its fidelity to the figure, foregrounding the importance of a generative process whose commitment to the figure no longer necessitates a faithfulness to the semantic regimes of years past – even if its byproducts may yield associations that cannot be controlled. In the context of this essay, the presence of the body and the stair are merely provisional figures whose presence in the discipline are demonstrative of this dilemma, and they demonstrate how the body is at once a visual and indexical register. If the index was conceptualized in a pre-digital era, then the digital contribution to the index was to systemically refine the modalities in which figurative constraints and outputs would become registered onto the body of architecture.