Speculating with Constraints: The Macallen Building

NADER TEHRANI

The design of housing remains one of the most neglected areas of inquiry in the United States over the past decades. With only pockets of significant work in practice and the academy, the discipline has mirrored a shift towards neo-liberal tendencies that have impacted American practices over the past forty years. With much of housing being relegated to private initiatives, even much of public work has been restructured around joint venture partnerships that seek economic viability as the driving measure of success in housing proposals. For this reason, most housing developments and proposals have revolved around known typologies and configurations, with little research or risk incurred. Often, the academic context has followed suit, adopting two dominant approaches, the first being mere acquiescence to the evolving commercial model (as witnessed mostly through urban design and real estate programs) and the second being a robust design research model, but rooted in formalism and often disengaged with the programmatic intricacies that make housing distinct from other architectural practices. There is, of course, a third evolving model that gains its agency through social engagement, participatory design processes, and community development, but that is often not paired with a design agenda. Indeed, without necessarily assuming that these positions are mutually exclusive, they are unfortunately an apt reflection of the relativism of practices today; they coexist with a sense of alienation, instead of forcing productive friction in the interest of advancing a cause larger than the sum of their parts. This essay speaks to the book’s commitment to bringing these different disciplinary spheres into productive conversation.

Despite this, or maybe because of it, there is a dire need for housing in most American cities in a variety of sectors, economic groups, and communities. A brief encounter with the range of demographic groups would also reveal that the way in which people live today varies vastly from the nuclear family; for this reason, most housing types do not directly address the evolving circumstances of programmatic, configurational, or functional needs. Having said that, one of the salient aspects of housing, in general, deals with the question of flexibility, in great part because of the dynamic changes in society over years, decades, and centuries. It is no accident that communities continue to thrive in forms of housing from the 17th century to the present with marginal needs for change. Most change comes in the form of the infrastructure of electricity, plumbing, and environmental systems which are often encrypted into the logic of the age-old structures without significant challenges. Still, if those very technical contingencies are taken with a measure of disciplinary gravity, they have also proven to be defining in terms of degrees of possible invention, if only because they are measured against the very constraints that provide for the necessary friction. As such, new building types have evolved directly from the balance of optimization of certain technical systems on the one hand, in tandem with formal and organizational play on the other.

It is important to note that there are, in fact, a range of architects –both practitioners and academics—undertaking significant work in this area; among them, Pier Vittorio Aureli has made the most compelling argument for the discrete challenges to typologies rooted in the principle of collective thinking. Jonathan Tate has engaged the potentials that are encrypted in the zoning and code bylaws of Louisiana to develop a host of dwelling innovations. In California, both Michael Maltzan and Brooks & Scarpa have extended the experimental traditions of L.A. culture towards housing for under-served communities. Of course, there are other East Coast universities still tackling the question of housing in their curricula, but with a dispersed set of agendas that do not always speak to the political challenges we face today. This book, as an extension of the eponymous symposium at the University of Pennsylvania, draws from the many facets of these and other practices to address such divergent themes as historical lessons, the changing nature of domesticity, the finance and policy behind housing initiatives, and of course the material manifestation of all themes ideas as they converge onto buildings.

This paper, then, will attempt to outline some of the theoretical tenets against which NADAAA has been able to test housing as a contemporary architectural discipline. It is, by no means, a thorough enough body of work as it draws from one case study, the Macallen Building; however, insofar as this building set forth certain ambitious agendas, it is also a good measure of how we might redirect our efforts going forward. As an outline, I will appeal to certain paradigmatic ideas that have driven this work, and how those may become relevant to other projects in the future. The first area of focus deals with the question of urbanism, the city, and its landscapes, and how various scales of community are implicated in the definition of housing complexes; here, the unit, the cluster, the building, and the neighborhood comes into conversation with an idea about the city—making housing respondent to externalities and part of a civic obligation. The second deals with the necessity of assessing emerging programmatic needs and how that may impact new building organizations, typologies, and hybrids. The third inspects the infrastructure of buildings, the systems that drive organization and their capacity to impact flexibility, what is often seen as ancillary, hidden, or in deference to the discipline of architecture; here, I will argue that speculative approaches towards the structural, mechanical and conveying systems become indispensable for the possibility of invention.

SCALING URBANISMS: FROM THE UNIT TO THE COMMUNITY

It is with a certain hypocritic oath that an architect comes to engage the city: perchance, not only to do no harm but indeed to catalyze urban opportunities and ameliorate conditions. How we achieve that differs vastly, and yet housing provides us with a scaled approach to urbanism that touches on the individual, the family, the community, and the entire city. Beyond the private realm of the house, or apartment unit, the role of public space looms large in this responsibility, allowing for many scales of interaction between the private and the public. As such, architectural gestures such as balconies, decks, courts, and plazas are all indications of a scalar ambition of interaction because each identifies a slightly different dimensional threshold between the individual and the collective. The Macallen offers a few, but important arenas in which this urbanism gets played out.

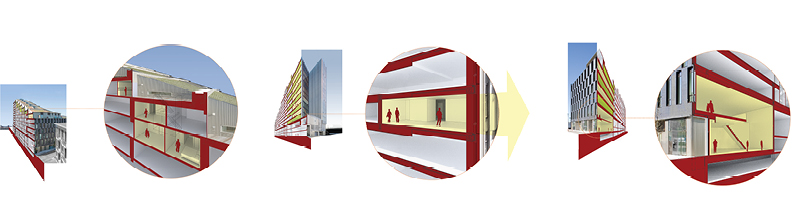

Located on Dorchester Avenue, a traditionally light industrial stretch of South Boston, the Macallen Building was to be the first of several buildings to encourage smart development next to the Broadway Red Line subway station. With the Fourth Street Bridge to its southern edge, the sidewalk ascends about twenty feet to cross over the railway lines to the west, setting up a sectional predicament with respect to the existing zoning ordinances, which as of right, only permitted a three-story height building on the plot. The Court Square Press building, located to the north of the site was the only veritable architectural context, an industrial historic brick structure that, through adaptive re-use, was renovated into lofts. Thus, the site did not offer any easy triggers to which to respond, and as such, opened up opportunities to explore massing strategies that violated the zoning restrictions, yet opened up a strategic approach towards housing on the site. The Sphinx-like figure of the building, thus, emerges as an interpretation of the site, with a tall tower on the west facing the skyline of Boston at its own scale, and a lower tail on the east, tangent to the triple-deckers of South Boston. A large raised courtyard on the north offers a relief from the Court Press Building, allowing the two buildings to come together with shared amenities including parking, a gymnasium, two common rooms, a screening room, a swimming pool, and a public deck for barbeques and gatherings. The same raised deck has individual garden units located on it, and this offers an opportunity to develop landscape thresholds between the public and private areas of the deck. At street level on the north, a paved plaza serves as a daily drop-off area, while maintaining the tactility and semantics of a plaza: on weekends serving for markets and street events. Maybe most importantly, on Dorchester Avenue, the strategic placement of live-work units that are accessible from both the street, as well as the building lobby on the interior, links the retail to the dwelling as a unique type. In this way, Dorchester Avenue is activated as a pedestrian street for the first time, and now in retrospect, has led to the development of ten new buildings that are following suit. The green mane of the sloped roof contains a punctuated series of large decks, belonging to the immediate units to which they are conjoined; these look out over the long distance into the harbor towards the archipelago of islands. On Fourth Street, smaller balconies populate the depth of the woven façade and offer added shade and acoustic remediation to the south-facing façade. In tandem, all these spaces of encounter define scales of the public realm, from the individual to the family, and from cluster to the community at large. For a building of ample urban challenges, they also attempt to create a sufficient buffer, and a deepened threshold, extending the inside out and absorbing the outside in.

PROGRAMMATIC TRANSFORMATIONS: TYPOLOGICAL HYBRIDS

Whereas the rationalist 20th-century housing structure is often characterized by notions of efficiency, repetition, optimization, and standardization, it also developed an ideal family unit around which to project organizations of houses and apartments. Recent data demonstrates that at least fifty percent of marriages result in divorce today, but further that many family units are more diverse in their organization than the nuclear family would suggest. For this reason, many households may include an in-law, a caretaker, a renter, or other such assistants. Other family structures are informed by different cultural lifestyles, be they part of LBGTQIA thinking, immigrant groups, or communal partnerships that share common facilities. In recent years with the rise of the internet, the role of the home office has taken root, and now with the pandemic, it has de facto even become the required convention; few dwellings have actually been designed to accommodate the actual necessities for work, nor the decorum that might be necessary for hybrid activities. With the rising costs of living, micro-units have offered an alternative to the excesses of the conventional apartment. Co-housing has also offered an alternative to the excesses of independent programs, and with ample shared space external to the unit, they offer the type of social engagement that can be provided by commons such as shared kitchens, dining facilities, gymnasia, screening rooms, decks, and other such spaces. Among other types, these are just a few of the organizational structures that are beginning to impact buildings, but almost never within one structure, as the culture and legal frameworks of buildings –whether as rentals, coops, or condos, defy the types of mixtures that is a fair depiction of our society.

Most importantly, what is often forgotten is the tacit acceptance of ideological biases that drive political decisions in the making of cities, and subsequently their housing. The process of districting, gerrymandering, and redlining all play a critical role in the definition of communities long before a building is even put to design. If communities were not already conceived around cultural, racial, and economic divisions, policies and laws often reinforce those divisions such that they forbid the kind of social exchange that might better advance the health of the city. Among other things, this is one of the most poignant reasons why American society suffers from racial inequities: indeed, these are as much legislated as they are culturally assumed. Architecture alone cannot address this, but insofar as formal, spatial, and material practices can embody certain values, and instigate ways of occupying space, the built environment serves as an index of who we are.

The commission for the Macallen Building emerged from a program that was conventional at best. The developer had already completed a proposal for two buildings that would work in tandem with each other: a tower on the west edge of the site and a lower bar building on the east, with a shared court in between. Naturally, as separate buildings, they would each require their own infrastructure of elevators, stairs, and services. The tower would contain most of the one and two-bedroom units, while the bar would also include some three-bedroom units. In contrast, our proposal conjoined the tower and bar building, and in doing so effectively eliminated the redundancy of infrastructures. By doing so, we also gained added space for the elaboration of more units and more variations in unit types such that the building caters to a wider array of housing needs. In effect, by minimizing the net-to-gross losses, we were able to internalize the gains towards better units, and a more sophisticated typological hybrid.

The law also mandates 20% affordable units to be included with the building, usually achieved through downgraded finishes. However, on closer inspection of the neighborhood, the community, and the potentials of the site, we were able to achieve three significant things: first to imagine a building figure that responds to the urban situation in a critical light, second to revise the zoning envelope as a result, and third to develop over a dozen unit types with the possibility of radicalizing its social mix. As a result, we were able to aggregate live-work units, lofts, efficiencies, one-bedroom, two-bedroom, three-bedroom units, skyline units, sky-deck units, and garden units along with duplexes and triplexes. As a development idea, it took a few risks in that it offered a wider range of low-cost and high-cost units, a mix that would not normatively be seen as favorable to the integrity of a building brand. Still, the marginal site of the building on the railroad tracks, next to the Red Line station and on the edge of historic South Boston, it had sufficient heterogeneity to be able to speak to different constituencies, defying traditional monolithic tendencies. As a hybrid organization, it also imagined that tenants of varied economic reach might be able to coexist within the same building, with units as low as $500 sq./ft. to as high as $1000 sq./ft. The cost variations were a result of predictable variables: space, views, height, and finishes. For this reason, the units atop the green mane formed may be the most desired of the types. Those are arranged as duplexes and triplexes taking advantage of the sloped roofline to create large open decks with eastern views. Much like row house organizations, these units smuggle typologies found in South Boston into the building, giving it a familiar semblance, and offering it the best combination of independent and collective inhabitation. Other units towards the base of the building gave other advantages at more accessible costs: open loft spaces without distant views, and a more engaged relationship with the noise of the street. However, it is this variation that defines the interesting results of the building, something that was further amplified by the economic meltdown of 2008. Indeed, it was precisely the flexibility of its infrastructure that allowed for new architectural accommodations and a new organization of parts of the building.

CATALYTIC STRUCTURES: THE INFRASTRUCTURE OF FLEXIBILITY

The organization of the Macallen Building derives from both top-down thinking, as well as bottom-up. The sloped figure of its profile is tall on the western edge as part of the city skyline, but as low as a row house on the east as it meets the South Boston neighborhood fabric. The internal configuration of apartments within this larger figure is anything but conventional: standard units are not stacked on top of each other, as would be in a modern structure. Instead, units are mixed on seemingly unorthodox stackings throughout: adopting a Tetris stacking system, the apartment units nest into each other in both plan and section, allowing for the programmatic and typological range we thought might enhance the opportunities of the building. More importantly, these units worked in dialogue with an infrastructural strategy that was unprecedented of this type, drawing on structural and mechanical approaches. From a structural perspective, we adopted a ‘staggered-truss system’ to achieve several goals: lighting the structure, prefabricating all trusses off-site, minimizing the number of footings, and ensuring a faster construction schedule than any other type of construction system. In turn, these strategies ensured lateral stability in both the longitudinal and lateral axes of the building without the introduction of sheer walls, thus allowing the passage of cars under the building within the garage. The space between each truss was seventy-two feet, allowing for unprecedented spans within which even long lofts could be placed. With short-span beams tying into the top and bottom cords of trusses every thirty-six feet, the module of the structure tied directly into the parking bays below the deck, allowing for three cars, every structural bay. In turn, the seventy-two-foot open bay above allowed for the liberal insertion of any unit type, as long as they complied with the mechanical mandates. The mechanical strategy was as precise as the structural: all plumbing, wet walls, and major ductwork were restricted to the inner corridor edge, adopting an absolute adherence to the vertical shafts to which they were assigned. As such, while light gauge steel studs can be re-situated to expand and compact unit types, the plumbing chases need to be respected with absolute fidelity. Metaphorically, the chases serve as a skewer that holds the varied meat and vegetables of a kebab intact in a linear sectional arrangement.

Flexibility emerges as a significant theme in this building, much as its legacy has sparked debate and experiments during the modern era. The decade that has passed since the construction of the Macallen Building has also revealed a few lessons. Originally conceived as a condominium project, the developer was slated to sell all of its units by the time of its completion. Indeed, it did succeed to sell 50% of them before 2008, but with the economic crash, a radical shift in the plan was necessitated: the remaining units needed to be rented for a period of time, making for an economic hybrid model as much as a spatial one. Because of the unique nature of the building’s infrastructure, especially its structural and mechanical layout, it became easy to make immediate transformations to the units. Light gauge steel partitions were summarily moved around for various units to add and subtract rooms in rental units, all while respecting the staggered truss system that was the building’s main structure. The rental period only lasted about three years, and during that time, all the remaining units were sold as the economy gathered steam. Other metrics proved telling also. As the first gold LEED-rated building of its type, it was designed with ambitions to build a community around sustainable ethics. With the calculated support of the developer, the project built its audiences, further enhanced by the management practices of the building. The pattern of interest in the building’s units is predictable: all units with views, outdoor spaces, and special amenities were the ones most sought after, and hence the most expensive. Most were sold beforehand, and the others soon after. The units in the ‘core’ of the building became the most economical ones: the south-facing ones due to the traffic on Fourth Street, and the northern ones with no direct sunlight. These were also the ones most prone to rentals during the transition period and with further turn-around subsequently. However, critical to these differences was a sense of orchestrated variety that ensured a wide range in its occupancy, ensuring a demographic profile with varied age groups, racial and ethnic backgrounds, as well as economic reach. More importantly, later post-occupancy narratives center around the inevitable schism between the projection of architectural intentions and the administration of governance by its evolving user groups; with the early years being characterized by diversity, the eventual condo trustee group was to be overtaken by a majority of empty-nesters, whose main political initiatives were to limit the use of the public spaces, to curb the times of their use, and to mostly disallow the use of many facilities by children –rooted in principles of liability, but in effect to bring bias to a dominant user group within the building, something that would eventually challenge the very diversity on which it was conceived.

Still, from an architectural standpoint, whereas one interpretation of flexibility is rooted in the idea of the generic, this building is characterized by two simultaneous approaches. The first is the distinction between heavy and light structural systems: that which the is main scaffolding and that which is temporary and kinetic. The second involves the sheer diversity of unit types, creating flexibility through fundamental choices of program, view, size, access to outdoor space, and a variety of amenities that demonstrate that we do not all desire the same things: flexibility through difference. This is a building whose programmatic potential is delivered on the ability to design, a priori, an approach to its infrastructural systems to catalyze a hybrid organization.

In closing, there seems to be a critical need to bridge practical and conceptual cultures, and housing can serve as a major instrument for this opportunity. With emerging challenges today, between the phenomenon of social distancing during the pandemic and the reinvocation of the long-standing social and racial inequities, housing stands to pose significant opportunities for formal, spatial, and material research. This case study interrogates some of the more seemingly benign elements of housing to reveal their instrumentality: that is, their agency to effect change. The Macallen Building is but a development, and certainly does not cast itself as a public housing project; yet, it offers certain pointed attitudes towards disciplinary internalities that have the ability to impact the politics of collective living.