UNFINISHED

Nader Tehrani

From the publication associated with the Spanish Pavilion entry and Golden Lion Award for the 2016 Venice Architecture Biennale (Edited by Inaqui Carnicero, Carlos Quitans, Angel Martinez)

Rem Koolhaas presented the exhibition “Elements of Architecture” at the 2014 Architecture Biennale with the intention of reexamining the fundamentals of buildings, analyzing the evolution of design in different contexts and different periods of time. This year, Alejandro Aravena will lead an investigation into the role of architects in the “battle” to improve living conditions for people all over the world with the exhibition “Reporting from the Front.” What do you think of this more social perspective on the role of the architect?

The social function of architecture is inevitable because it is the foundation from which our work as architects has always evolved. That it has become the focus of this particular Architecture Biennale is probably the result of the need to re-examine the agency of the discipline and its impact on the world, but also a reaction to the many prior Biennale’s eclipsing of these very issues in lieu of disciplinary arenas of advancement, whether they be technological, formal, or material. The irony is that the “social” is often used as a euphemism for the lack of a design agenda in architecture; certainly this is not the case for Alejandro Aravena. If anything, he is actually the most guilty of all the architects out there, with “designerly” impulses that consistently generate a form of surplus from within the discipline; his dexterity with form, tectonic systems and even iconographic play bear witness to the kinds of architectural motivations that cannot be reduced to social responses if seen from a reductive point of view. Maybe it is Aravena’s delicate dance between his political activism and his architectural ingenuity that makes this theme so poignant: he has managed to seamlessly align these two poles into conversation. Thus, for all the press that claims social priorities, they often miss the actual instrumentality of the design work he brings into focus; conversely, for all the press that has questioned his elimination of relevant design agendas, I think that Aravena, the curator, did try to articulate this point, underlining where design matters and how its devices are instrumental to a larger social function.

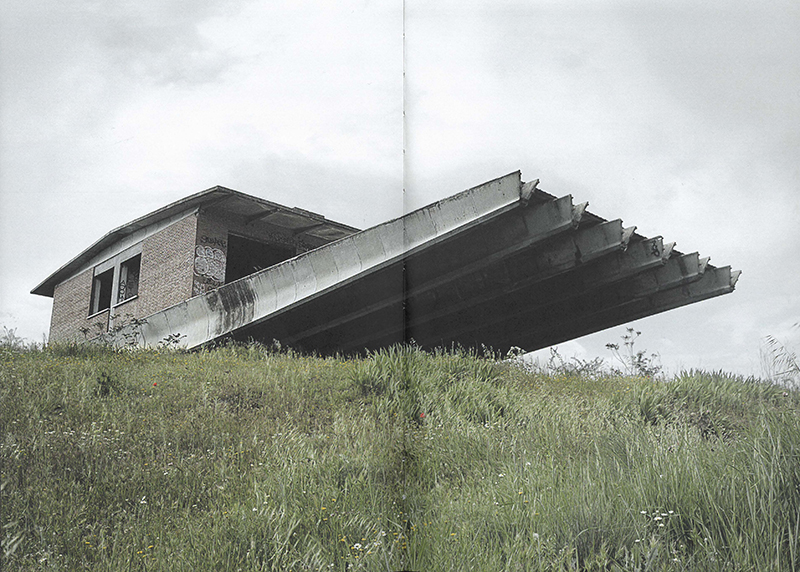

The Spanish Pavilion responds to Aravena’s call to speculate on the major architectural issues of the last ten years. After a building boom driven by a period of high economic growth, steep economic decline resulted in a lack of demand and resources needed to maintain many unfinished constructions. This [situation] rendered a collection of contemporary ruins and neglected spaces across Spain.

Do you think this consideration of time is present in contemporary architecture? Should architects be responsible for dealing with the fact that social and economic contexts and the functional needs of new construction may change over time?

Notions of time and incompletion in architecture tap into two interrelated themes in which I am interested. The first is about designing for expansion, and the second is the idea of flexibility, something that was latent in historic typologies, but that was also expanded on in the 1960s in a more self-conscious way.

The first goes back centuries, but takes on a different charge with the invention of steel and reinforced concrete structures. Much of the modern and contemporary construction in developing countries, from Iran to South America, is premised on the fabrication of “incomplete” structures-anticipatory buildings that are over-structured knowingly to expand from single-story structure to two-, three-, or four-story buildings. These structures anticipate growth as families increase in size, see generations grow within a common structure and even incorporate their business and other sources of livelihood within them. This perpetual state of incompletion is often a central part of the identity of certain cities; as such, they cannot be seen as incomplete cities per se, but rather cities conceived in evolution. They look provisional because they are designed to be flexible.

The idea of flexibility is not necessarily about the urgencies of the economic moment, even if it has the power to respond to them, but the persistent anticipation of what will happen next. It reflects the inevitability of growth. It reflects the promise of financial wealth or even its loss. For architects, this is interesting because typologically flexibility resides in many aspects of our discipline.

Tensions between the fixed and the mobile, the permanent and the impermanent, are part of a much larger historical trajectory that, because of the forces and speed of modernization, is accelerating. Consider the rate of growth of cities in China, for instance, where rural cultures have been supplanted by megacities in less than twenty years: how do these cities imagine their own transformation as they foresee transformations in their economy, needs and fluctuations? How would an economic crash at the scale that Spain has recently seen impact these new cities?

Understanding the poignancy of the question of time in Spain, especially as materialized in the work displayed at the Biennale, one can measure it in various scales. It is certainly not only registered in the projects that succumbed to the economic crash, even when their architecture was able to deftly navigate an apt response through austere measures. It was also in the way in which the longue durée was implicated by historic structures that are repurposed toward new uses and cultural mandates. Within this process, the nuances of preservation, renovation and intervention have played themselves out in complex and inventive ways, often showing how the constraints of the economy might offer even more powerful alibis for ingenuity than the frictionless alternative of opulence.

Titled “Unfinished,” the exhibition in the Spanish Pavilion draws attention to these contemporary ruins in order to discover principles for design strategies. “Unfinished” promotes creative speculation about how to subvert the past through [positive] contemporary action, exhibiting architecture developed in Spain during the last seven years.

In these projects, design emerges as a response to preexisting conditions while remaining open to evolution over time. The speed with which we commonly evaluate society’s developments and the urge to constantly reinvent affect our perceptions of architecture. How do you position yourself with regards to the contradiction that exists between the architecture commonly presented by the media as finished forms frozen in time and architecture that has the capacity to evolve, adapt, and transform?

The idea of the unfinished is invariably also associated with scarcity. When resources are limited, when you know that the fundamental structure of a building may cost more than 60 percent of the budget, or when you know that the mechanical systems are going to drive the form of the building, it suggests radically different approaches in building priorities. If you have no control over the architectural assemblage of parts, you may elect to decorate the surface as a last resort–what many do as the main project of architecture in this day and age. Or alternatively though inelegant as it may seem, you may invest in the building’s infrastructure, raw and unfinished as its results may be. The latter offers the possibility of an eventual process that may yet complete, evolve, or transform its state, while the former mummifies it, rendering it into earlier obsolescence.

It is interesting that this is all being discussed in relationship to the “social,” because I relate to it from a completely different perspective: the “value engineering” process very common in the United States that often drives a wedge between designers, fabricators and the clients/users. While its intentions are to optimize resources, to protect design intent, and to build collaboration between the various players in the design process, it is more often than not also a vehicle that separates the architect further from the means and methods of construction. Often, outside consultants are brought in to evaluate the design, and from a different mindset than that which formed the priorities of the project in the programming and design process. The disparity in mentalities often results in “design features” being seen as a surplus, as unnecessary, or as frivolities. In this sense, it overlays performance criteria that only underline the bottom line–not the cultural values that drive the design as a more cohesive project.

What would it mean to undertake an “intellectual value engineering” process at the beginning of a design, such that there is no need for architectural finishes? The finished project as unfinished! What mechanical model would you arrive at in order to complete a building in a state of incompletion? I think that is something that is provoked not only by your question, but by the theme of the Architecture Biennale in general. There is, of course, an implicit metaphor in the question. In architecture, there is a concept called “finish”: the project’s finishing veneers, and that which gives it character. The plaster, the wood sheathing, the stone, for example–if you like, the skin of the building. The assumption in most construction today is that it is composed of a system of frames and veneers, building up walls as composites of layers, among which the finish is but one element. This also means that if one were able to dispense with certain layers, or those found to be redundant or extraneous, then we would focus on that which is irreducible. Any attempt to find the fundamentals of the necessary are also in vain, since the current legal and technological requirements for insulation, and energy control, not to mention waterproofing and other elements, such as vapor barriers, are at odds with the notion of a raw or unfinished building. For this reason, the impulse to drive the building back to a state of the indispensable is, in many ways, diametrically opposed to the evolution of contemporary technologies. I think that we are at an interesting moment, balancing the urge to look forward to the future while also looking back to the elements. If we think about the range of responsibilities we are confronted with, whether for a client in a state of wealth or a nation in a state of poverty, architects deal with the ethics of spending resources as a critical part of their design strategy, and effectively the state of incompletion can be seen as a proactive strategy, rather than de facto liability. That is a critical question about the indispensability of design: What is the least action we can take to yield the maximum payback?

Robert Venturi recalls Paul Rudolph in Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture saying: “All problems can never be solved…. Indeed it is a characteristic of the twentieth century that architects are highly selective in determining which problems they want to solve. Mies, for instance, makes wonderful buildings only because he ignores many aspects of a building. If he solved more problems, his buildings would be far less potent.”

When you look at architects succeeding in the international scene, do you think their success is a consequence of being very selective in terms of which problems to solve and which to ignore? Do you think architects should be selective according to their own approach or according to society’s needs?

The assumption that architects exclusively solve problems is a huge missed opportunity. It is, in part, how we pose questions and how we reformulate problems. If we are only to respond to society’s problems as they are delivered to us, then the questions are already formed. We should ask: What questions should architects ask about society such that they transform society in the process? In doing so we are not solving problems that are assumed to exist, but we are creating new questions that pose the possibility of generating new forms of inhabitation, new forms of economics, new spatial and social relationships, and new ways of inserting architecture into the world.

I am thinking about how Edward Said talks about “worldliness” here and how architecture is invariably a social and political instrument. What is architecture’s agency? We should to be able to clearly describe how our use of form, space, materiality, and organizational systems impacts the types of questions we pose, such that these problems are transformed through our instruments.

I suspect Aravena might reinforce this view; he looks at the world, and imagines what architecture can do through its techniques. Accordingly, he formulates new questions, but through architecture. He is not an innocent problem-solver either; he is much more strategic in the way he reformulates questions. Beyond the lure of positivism, his questions are not reducible to the determinism of simple responses or the linearity of thought that evades the complexity of multiple narratives.

I think that the richness of architecture has more to do with its speculative possibilities, its iterative nature, and its multiple interpretations. What is beautiful about the Paul Rudolph quote is that it underscores the bias that we each bring to our architecture. There is no architecture of perfect proportion. The only time we have architecture is when something is too big, too small, too bare, or too excessive.

Intending to remove certain architectural elements from the equation, the Spanish Pavilion announced a call for projects looking at buildings and structures developed under the constraints of the economic recession–architecture without a site, without cladding, without new materials, without new space. The result has been quite unique, defining a new spectrum of innovative design strategies developed under constraint. How can we evaluate the quantity and quality of new versus existing architecture?

The tension between new and old buildings, and how we reconstitute the city in terms of deploying resources, is instrumental; buildings have been used, reused, and programmatically redefined for centuries. Consider Aldo Rossi’s use of the Piazza del Anfiteatro in Lucca, Italy and how it transformed over centuries, from a public arena to residential units, adopting the radial structural system of the arena as party walls for the houses. Great organizational systems and potent typologies have this resilient ability to take on multiple lives, and somehow withstand the cycle of obsolescence that comes with technological accessories.

But this question also addresses the broader relationship between preservation, renovation and intervention, and the varied ethics involved in negotiating them. Sometimes, in the process of preservation, we have to rediscover techniques of construction that are long gone and obsolete–in effect giving life and continuity to certain trades. At the same time, most historic buildings are led slowly into obsolescence if only because they are drawn out of compliance with new fire and egress laws; finding creative ways in which to insert these requirements into old buildings requires a nuanced ethic of renovation that might produce a more stealth approach–again, giving new life to the building. Naturally, there are also moments when new interventions are necessary, without which new missions, programs and requirements simply cannot work; as such, a clear attitude is also required to articulate the insertion. Consider the canonical work of Scarpa in Castelvecchio, and how the project objectifies the new insertions within a historical carcass, respecting both the new and the old. These three modalities of thinking all offer ways of engaging the culture of preservation as animate, alive, and progressive. It is another lens into the idea of the unfinished project, in perpetuity.

What draws you most to Spanish architecture? What aspects of Spanish architecture do you consider to be most unique? And the weakest?

There is an aspect of Spanish architecture that fascinates me, especially in the more speculative works as characterized by figures such as Antoni Gaudi, Miguel Fisac, and more recently Anton Garcia Abril and Debora Mesa. In this tradition, architecture is conceptualized through its material agency with the idea that it might advance the discipline in unanticipated ways. At once experimental, and materially inventive, it was also an architecture that delves into engineering sciences while expanding the way we can think about the discipline.

There is also another tradition of modernism in Spain that is maybe more orthodox. Whether this set of values was planted early in the twentieth century or whether it was well-guarded by the relative isolation that Spain experienced in Franco’s years, it also has its revival in the post-Franco years with the re-inauguration of the Barcelona Pavilion by Mies van der Rohe. Whatever are the circumstances that produce such cultural consensus, it is also something that gives light to the level of consistency that we see in the selected projects for the Biennale: How can such a vast array of architects achieve such unity and excellence, given their diversity? Within this tradition, invention happens within a more well-established forum, where certain values are assumed, a common language is spoken and the architecture speaks to other architectures as a basis for both confirmation and critique.

There is, also, of course the new generation of Spanish architects, and they are looking at the history of both the Spanish peninsula and modern architecture more broadly and challenging it from many perspectives: technological, organizational and environmental. Thinking just of a few, from Selgascano to Andres Jaques, and from RCR to Ecosystema Urbano, all somehow educated under the rigors of classical modernism and yet all in their own way overturning the very orthodoxies in their own manner, challenging not only the questions posed by the previous generation, but also the unity of expression they offered. It would seem that this generation benefited from the closure of a well-disciplined tradition, while also falling into practice at the critical moment when the Internet gave way to global communication that unleashed a wider and more panoramic theoretical field for them. What is clear though, is that despite the more recent adventures in global discourses, the virtuality of space and the reliance on the Internet, that these architects are still somehow deeply invested in the physicality of architecture, the materiality of its specification and the discipline of its commitments.

What do you think are the main challenges Spanish architecture will encounter in the future?

If l am not wrong, Spain has an institution called the Colegio de Arquitectos. As an instrument of power, it maintains legal jurisdiction over what the profession can do, and though it functions in part like the AIA in the United States, it seems to offer much more power, consistency and advocacy for architects. In this sense, the AIA is effectively very weak.

In the USA, much of practice is organized around the idea of risk; many cannot gain access to work, because they cannot afford the right level of insurance. The idea of a lawsuit is not the exception, but a rule even. This often inhibits the speculative potential of architecture, how it can contribute to society, and more importantly how it can produce new forms of knowledge. That is the risk that Spain faces as its economy becomes more globalized–if that is, the power of the United States and some of the more conservative tendencies of the EU come to bear their weight on the profession in Spain. For this reason, I continue to be fascinated by the relationship between progressive institutions in economies that are less developed, as was the case in Spain some years ago. They are able to build in much more speculative ways and yet rely on a framework that is at once powerful, yet permissive.

Does it make sense in the globalized world to talk about architecture in national terms? What does the term “Spanish architecture” mean to you?

Our conversations have been global for many years. I can hardly say that I come from one country: my parents are from Iran, I grew up in South Africa, I was educated in the United States, and my professors were Argentinian. We speak many languages and the work we produce is a response to our hybrid cultures.

The coherence of Spanish culture, as a peninsular nation, is unique. The Pyrenees and Franco helped to separate Spain from very close neighbors in curious ways. At the same time, Spanish architecture references traditions beyond its borders. In that sense, we don’t need to dichotomize between the local and the global. These realms permeate each other in quite complex yet concrete ways. As we reconstitute ourselves in relation to global challenges, we also realize the degree to which our politics only gain traction at very local levels, and this tension between the two is certainly playing itself out in Spain also. In this sense, talking about architecture in national terms seems somewhat out of focus, despite the wealth of consistency that Spain has offered.

What are Spanish architects contributing to American academia?

Beyond their leadership in our schools of architecture over the years, the new generation of Spanish architects is already changing the face of architecture in the United States. You have already seen them winning the PS1 competition and on the cover of Architectural Record magazines, and these are but a couple of random examples within the new generation. Many of them, young as they are, have had a good deal more experience in building, and this has had an impact on the way in which it is impacting both faculty and students in the American scene–not simply to build, but to pose questions through building, to experiment through it and to produce new forms of knowledge through it.

It should be underlined, however, that this new generation is anything but monolithic. Instead, we are witnessing many voices and it is impacting not only design culture, but research and history and theory alike.

What would you say to young, recently graduated architects struggling to find a footing in a troubled economy and architectural landscape?

What distinguishes this era from the generation prior is the role of communication and technology in the education and worldliness of architecture students. This agency has afforded many young architects the power to transform practice from the bottom up, rather than work under somebody for twenty years. New partnerships are also forming across states and countries, giving young architects the agility and dexterity to react to site-specific and culturally remote areas in a more hands-on way. All in all, the ability to produce with an output that is unprecedented has catapulted the new generation to be able to take on an immense set of projects and challenges that would have been very unique in another age. My advice to the young graduate would be to look closely at these opportunities, since they afford them amazing access to an architectural practice that is more broad and diverse than ever before.