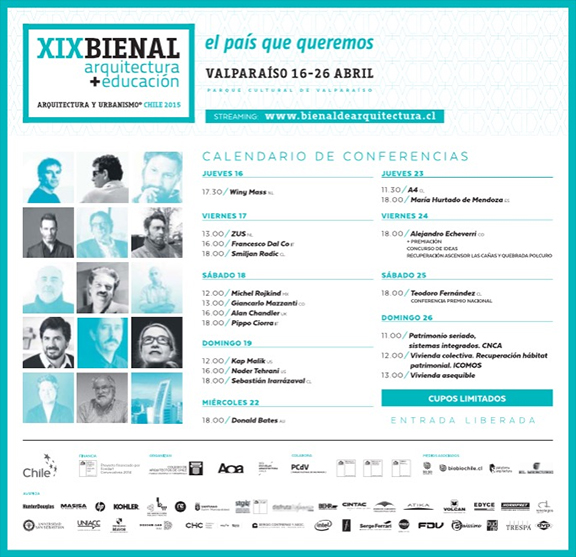

Since March 1, I have read Casey Ross’ A New Age for an Old Town dozens of times. The Boston Globe feature is interesting on a number of fronts; Mr. Ross describes our current “golden age of building” within the context of earlier waves of the 19th and 20th centuries that produced some of the city’s most beloved landmarks. He takes us back to the 1964 construction site of the Prudential Tower, and even quotes John Hynes referring to Boston as the “Athens of America.” The best thing about the article however, is the link to the sidebar graphic – a collection of articles chronicling 52 buildings that have either been provisionally approved or have actually started construction. There is remarkable similarity among the images, and it is tempting to sort the buildings into piles: the plane-slippers, the wrapper-shifters, and the skirt-lifters. In short, most are variations on the theme of maximizing a floor plate.

According to Casey Ross, and generally backed up by the BRA website, there is 34 million square feet of new building in the near-term Boston pipeline – this is Boston alone. Imagine if we could add in Cambridge and Somerville. Within that number are other interesting stats. At least 7 of the proposals are legitimate skyscrapers; 63% of the projects have a significant residential component, and most often the housing is paired with a hotel. There are 29 development teams financing these projects, although there are recombinations and LLC’s that make it hard to count the players. In a subsequent letter to the editor, architects Mark Pasnik and Michael Murphy note that Ross’ list of projects illustrates that development is an “insider’s game.” They point out that two architecture firms are producing nearly a third of the 52 projects but stop short of revealing that Elkus Manfredi is involved with 25% of them. In total there are about a dozen firms in the mix, with Miami’s Arquitectonica winning the “traveled the farthest” award.

If it hasn’t happened already, the City will soon designate a development team for the Winthrop Street Garage. Ten years ago we would have called this Trans National Place. At that time, developer Steve Belkin had engaged Renzo Piano to design a 1,000 foot tower. The details of that project are the stuff of legend, and the upshot is that one cannot build a super-tower so close to Logan Airport. Nonetheless, Belkin gets points for raising the architectural bar. The original proposal had elegant proportions and tectonic heft that somehow gave unity to the eclectic volumes of Downtown. The reincarnation of the project promises to be both shorter and less inspired, but it will nonetheless take its place on Boston’s skyline as a marker of this our 21st century “golden age of building.”

Trans National Place designed by Renzo Piano

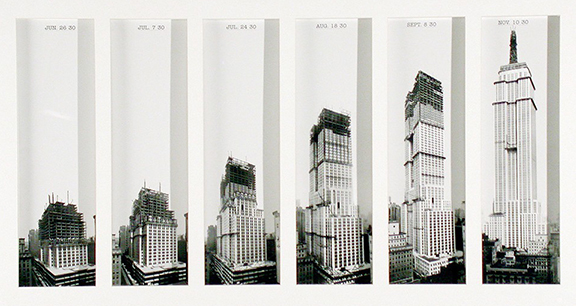

Harvard professor Edward Glaeser wrote that “(r)eally tall buildings provide something of an index of irrational exuberance,” and he points to the iconic Empire State and Chrysler Buildings as examples. To his point, towers generally go up in economic boom times, and emerging economies continue to show their might by sponsoring increasingly stunning and tall buildings. In contrast, Boston towers do not tend to be particularly tall, and the City seems not to see them as icons of our urban greatness, which is a shame because once it is up, a tower becomes an indelible part of our identity. Much as we might like to erase One International Place, it’s not going anywhere.

Construction of the Empire State Building

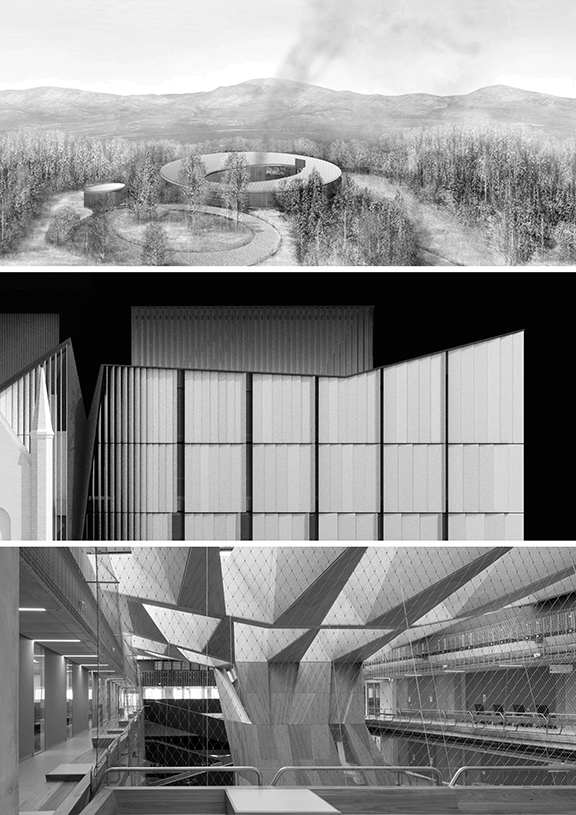

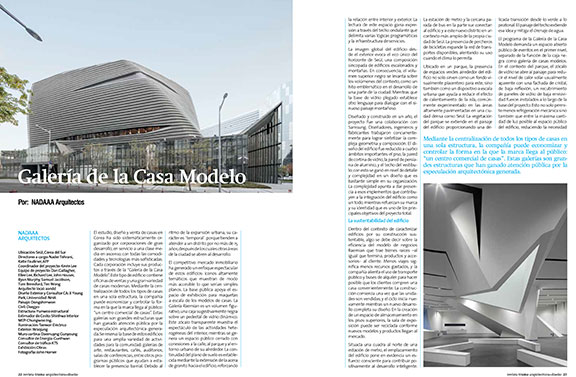

As I was penning this blog, Rachel Slade published her scathing “Why is Boston so Ugly?” piece in Boston Magazine. This is the article many of us have wanted to write but could not articulate. She called out the visual affront of 111 Huntington, and the lost opportunities of the Seaport District. The conventional wisdom that it is hard to get anything built in Boston is called a bluff. It is actually ridiculously easy to build just about anything if you know the right people. Ms. Slade takes on the BRA and exposed the long tenure of the BCDC members. Most endearing was that she listed NADAAA among the “most vigorous design firms,” although I did not appreciate her assessment that firms like ours lack the capacity for big buildings. Capacity is not the issue. Jonathan Levi Architects won the Harleston Parker medal with an 84,000 square foot public school and the firm has designed millions of square feet of institutional, residential, and educational buildings. Anmahian Winton Architects have a high-rise under construction in Ankara. David Hacin has mid-rise residential buildings all over town, and is in fact one of the prospective design teams for Winthrop Square. NADAAA just completed the 250,000 square foot Melbourne School of Design, the result of an open international competition, and has larger projects in design and construction. What binds the work of these firms together is not their relatively small size. The common thread is architectural intent, which unfortunately has become separated from the merely functional as if to say that the added value of design is luxurious excess. Undaunted, Rachel Slade looks for bigger fish out of town and references significant buildings in New York and Chicago, cities with a legacy of great architectural ambition and civic pride. In her assessment, Boston comes up short and she is right. With notable exceptions, Boston developers are generally indifferent to design. At a ULI meeting last year, a prominent Boston developer admitted that ultimately he does not care what his buildings look like. There are complex negotiations, oversight agencies, fickle markets, and prescribed profit margins to be dealt with — this is perhaps why few locals hang out in the Seaport District. Ultimately one does need to care.

Ankara Office Building designed by Cambirdge-based Anmahian Winton Architects

Melbourne School of Design by Boston-based NADAAA

The combination of the current gilded age with a new administration has provided an opportunity to correct the trajectory of the current building boom, and there are guiding principles to light the way. First, Boston’s built environment should reflect the region’s rich culture, and the ambition of what we’d like to be. Architecture carries the weight of history as well as the demonstration of invention, technology and civilization. Related to this is the obligation to be respectful of the historical layers of our urbanism without being imitative or mocking. Second, it is incumbent upon all constructors – designers, policy makers, and builders – to respect a kind of Hippocratic oath. Do no harm, and when possible advance social well-being. Architecture has the power to mediate certain landscape and urban challenges in ways no other medium can. Consider the legacy of Mecanoo/Sasaki’s Bolling Municipal Building. Surely it deserves some credit for the fact that for the second quarter in a row (according to Boston Business Journal), Roxbury’s Dudley Square neighborhood ranked as the Commonwealth’s hottest real estate market. Finally, one should not separate the functional from the courageous; a well-designed building is not a luxury, it is a basic right like clean water, functional infrastructure and access to the Internet. By separating the practical from the beautiful, we are all but guaranteeing bad design, undermining our potential as a progressive city. When our own mayor joins the chorus by calling Boston’s latest bumper crop of buildings “merely functional”, it is time to expect more.

Mayor Marty Walsh, photo from Bostoninno

Comments Off on New Age Old Town