Introducing the work of John Hejduk at The Cooper Union would appear to be an easy task, if a bit redundant, but if measured by the many protagonists that emerged from the generations that have walked these halls, then it would seem even more challenging coming from the one voice whose difficult mission it would be to occupy his shoes. Now almost two decades after his departure, the sheer advent of time has invariably forced us to revisit his presence, but this time through the lens of history.

The work of Hejduk was multi-faceted; it came in the form of words, drawings, installations, buildings and, more importantly, pedagogies. His definition of the social contract came through the act of giving: he gave his time, patience and ideas through the production of knowledge, and over thirty-five years of dedication produced a “school of thoughts” that has created many teachers, architects and thinkers of exemplary qualities. In great part, that is arguably Hejduk’s greatest achievement, giving life to the myriads of voices through whom we now experience new forms of debate, architectural inventions and emerging pedagogies.

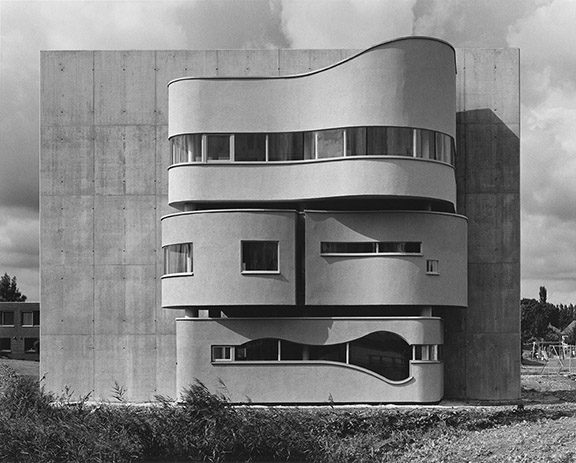

With Hejduk’s generosity came a space of dialogue and collaboration. It was David Shapiro’s words that would prompt Hejduk to give formal, spatial and material substance to the House of the Suicide and the House of the Mother of the Suicide. It would require the tectonic tenacity of Jim Williamson to situate and translate raw sketches into constructive drawings for the eventual fabrication of the two structures. Certainly, it would also require the eyes of Hélène Binet to reinvent the structures: to give light, weight and depth to them as our eyes could not otherwise see.

This exhibition brings these forces together in Cooper Square, where the Jan Palach Memorial has been installed, in the Second Floor Gallery where the timeline of its various iterations gain historical clarity, and in the Arthur A. Houghton Jr. Gallery where the work of Hélène Binet sets the stage for the work as part of a larger body. While Binet is often introduced as the documentarian of Hejduk’s work, this exhibition demonstrates inversely how she also adopts him as muse, if only to manifest a sustained and patient temporal gaze on a dedicated oeuvre.

From our perspective today, the lens of history offers us this opportune overlay of four characters whose strength of vision and commitment brings forth a collaborative narrative that sustained over three decades, while commemorating events of 1968 that sparked an era of resistance. If the social and political messages that are ingrained in these structures do not sufficiently demonstrate the ways in which an architectural project embodies a commitment to varied forms of disobedience and defiance, however obliquely, then their reconstruction can be a simple reminder of the political transitions that we are living through today, if only that it prompts us to gauge the very predicaments and decisions that surround us as history is being recast on a daily basis.

As we revisit the forms of the Jan Palach Memorial, we see in their strangeness a certain familiarity; that is the plight of architecture, as history situates—and saturates—its forms with particular associations. But we are reminded constantly of their once de-familiarizing presence, anthropomorphic characters invented to act on the urban scene as no other architecture could, if only to remind us of other possible realities we could inhabit. But, it is also a reminder that we face this very challenge again today, projecting against a new reality.

-Nader Tehrani, Dean

The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture

Comments Off on THE PROJECTIVE ALLURE OF HISTORY