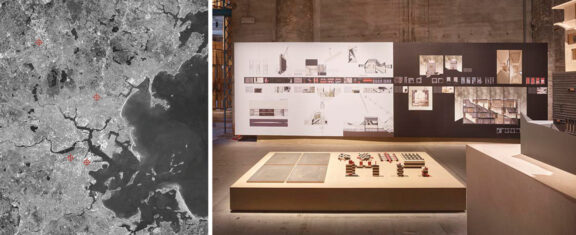

The Venice Biennale Architettura 2021: How will we live together?

Other Ways of Living Together

By: NADAAA

Arsenale, Interior

The built landscape has taken on a global scale. There is little on the earth that has not been impacted by the human footprint. How we live together and where we live is described by great environmental diversity from the urban to the rural with the suburban and industrial territories in between. There are certainly other spaces also, but the predominance of these four stands out, and we have examined them with a few principles in mind.

The first revolves around an ethic of Existenzminimum whereby the density, flexibility, and efficiency of residential buildings are challenged once again from an architectural vantage point; a legacy of the 20th century, this is a moment of reckoning in relation to current environmental and social challenges.

Secondly, because of this first ethic, many typological conventions and code constraints may require reconsideration in order to imagine other ways of living together. We have probed certain loopholes in each case

study to unleash certain plausible eventualities, drawing from common standards, but overturning them in the interest of invention.

Thirdly, all these studies emerge from a common interest in working with naturally renewable resources. We have worked with mass timber, in particular the relationship between cross-laminated timber and stud framing, the first being described by the combination of structural and thermal mass while the second being characterized by its hollow cavity, enabling the threading of mechanical, electrical, and plumbing services within a structural wall. Traditionally seen as independent or mutually exclusive, here we will present these two systems as symbiotically co-dependent.

The sites of these studies revolve around the greater Boston area, but their implications may be as relevant for many other international regions.

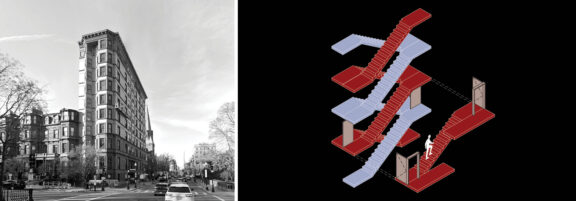

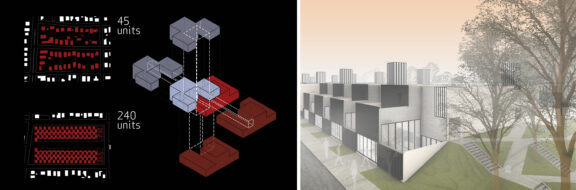

THE CITY CENTER: THE VERTICAL ROW HOUSE

Similar to other urban centers, Boston has developed almost all of its inner-city infill sites. Thus, we are tapping into opportunities for rewriting zoning by-laws for urban corridors that are already tall in nature due to historical circumstances and acquiring air rights in areas that might

benefit from higher density. Such is the case on Washington Street in Boston’s South End where we propose establishing a building height that is double the neighboring row houses that will serve as a point of orientation for Worcester Square.

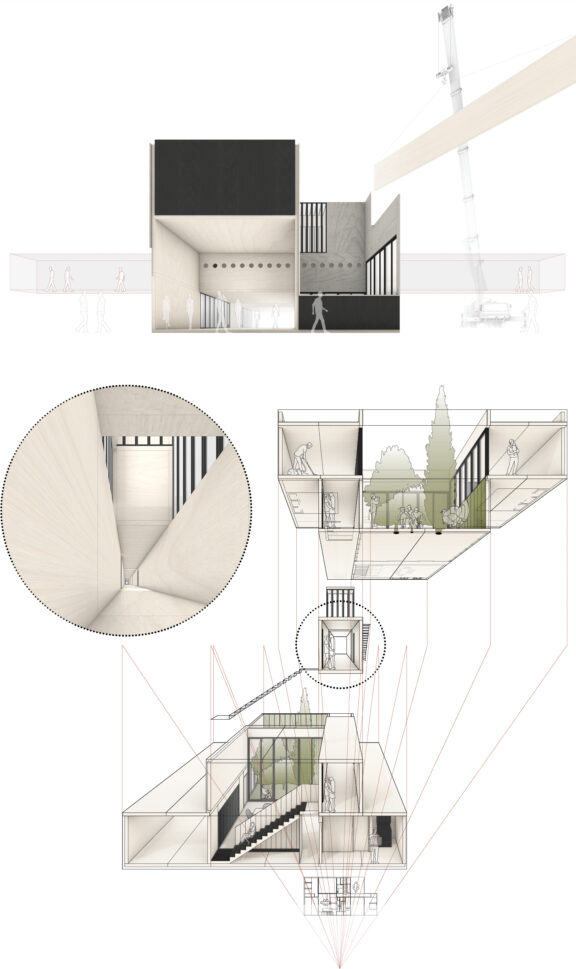

The mandate of two means of egress defines one of the indispensable elements of safety in residential structures. The double-helical fire stair serves to radicalize the efficiency of two means of egress contained within the same footprint. However, never before has the fire stair also served as a communicating stair between two floors of the same unit—or alternatively a communicating stair between two apartments on different floors that might be refashioned as a single unit.

With the introduction of added fire doors, the centerpiece of this vertical “slab” building takes advantage of this loophole to create a loft unit that is defined by a double-height living space in combination with a side ambulatory that can be separated into three bedrooms. The efficiency of the typical South End rowhouse is maintained in the tower at 84%. However, the number of bedrooms is tripled to 21 from 7 by up-zoning and hybridizing the double-helical fire stair (both public/private space).

A TOWER OF 14 BEAMS: The structure is composed of an envelope enclosure of cross-laminated timber, hybridized with infill walls of stud framing providing hollow cavities

for the MEP systems. The structural envelope beams are 8 feet deep and span 80 feet and are visible from the street as the main image of the building.

THE SUBURBS: A DENSIFIED MAT

The suburban condition of Revere, Massachusetts is composed of residential lots, replete with front, side, and back setbacks that are an embodiment of the American dream: the prospect of one’s own lawn. And yet, ironically, with a front lawn that is socially evacuated, and side-lots that cannot be inhabited, it is only the backyard that offers the respite of an outdoor room. With an emphasis on

densification, this study eliminates those unused spaces, while optimizing circulation and ensuring that every unit has its own private outdoor room. The history of the mat building is illustrated by many examples the qualities of which are urban in their embodiment of roads, alleys, walkways, and outdoor rooms, the combination of which is an attitude towards the making of the city.

Drawing from Zolotov and Havkin’s model neighborhood in Be’er Sheva our proposal is composed around a central skylit corridor, running the length of the block, from which all units are accessed. All apartment units are U-shaped, interlocked in plan, and section around individuated courtyards facing in opposite directions.

Opposing units can be connected to each other to create larger units of four bedrooms with workspaces. Sharing corridors and inverting outdoor spaces into courtyards allows for an 85% efficiency. The unit planning facilitates an aggregated mat configuration to have a density of 6 times the typical suburban block.

Collectively, the block contains several communal spaces that offer relief from the private quarters of the courtyard configuration. The inner block contains a green common for the entire block, inclusive of planting areas, dog area, children’s garden, and a lawn. The undercroft contains common parking, one level below grade, punctuated by two public arcades at street level that cross through the block.

These arcades contain the basic services of a residential block, inclusive of daycare, pharmacy, grocery store, and basic needs. The street facades are activated by live/work spaces on the ground level, offering varied ways of programming the sidewalk: studios, cafés, small offices, or other commercial activities.

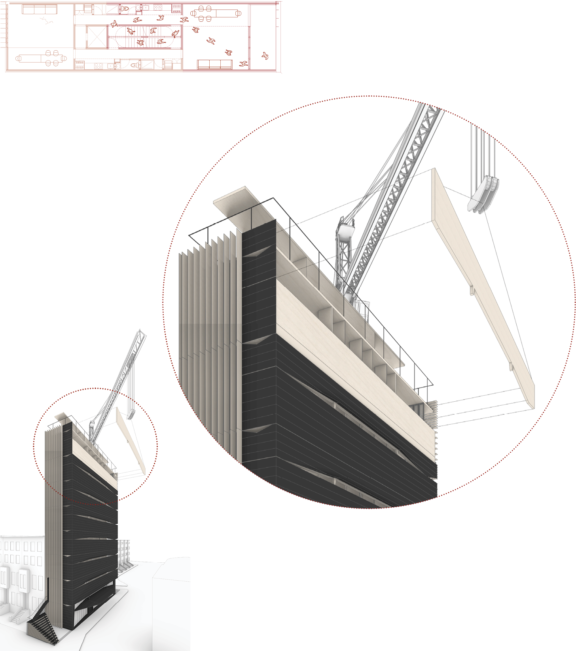

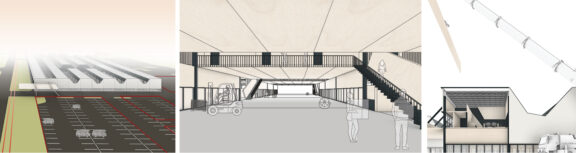

THE INDUSTRIAL SITE: BIG BOX ADAPTATIONS

Of the phenomena that the pandemic has unleashed, one stands to become the new normal: the substitution of large-scale shopping in favor of delivery of basic goods. Big-box stores such as Costco stand to become taken over by the economies of Amazon and other delivery-based businesses. The question is whether the millions of acres devoted to the big-box stores stand to be demolished, or alternatively re-used and adapted for new uses. This

proposal assumes the latter and maintains the big box intact, inserting a second floor hosting efficiency units within it, with the idea that the entire first floor may remain open for light industry. Composed of small businesses, artist studios, and workshops, among other possible workspaces, the ground level is maintained as is, with large lofts that can easily be subdivided and reconstituted in larger and smaller units at will.

The big-box adaptation introduces a microcosm of the city into an industrial shell. Inserting a cross-grain of program turns 100% commercial into 28% housing 72% mixed: civic, light industrial, and commercial programming. The 132 loft apartments across an expansive single-story

facilitates an efficiency of 81% compared to a typical high-rise efficiency of 60%. The hybridization of programming also allows for the re-zoning of neighboring lots, allowing for the development of new streets, transportation systems, public spaces, and supporting lots.

The Big Box characterized by ceilings at heights of 27 feet allows for the introduction of loft units 14 feet in height above the flexible space of commerce, fabrication, studio/maker spaces, and light industry below.

This is made possible without the demolition of its structural system, but rather the mere addition of CLT beams and slabs that set up a parallel structural system within. This new structural system is slipped into the building as if stored on their existing racks.

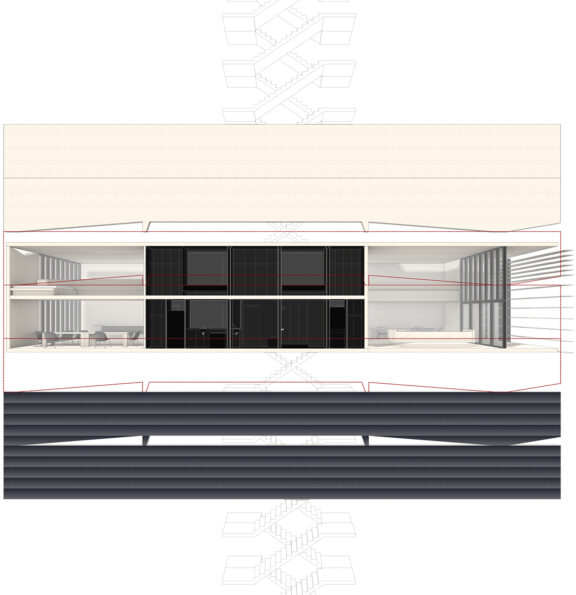

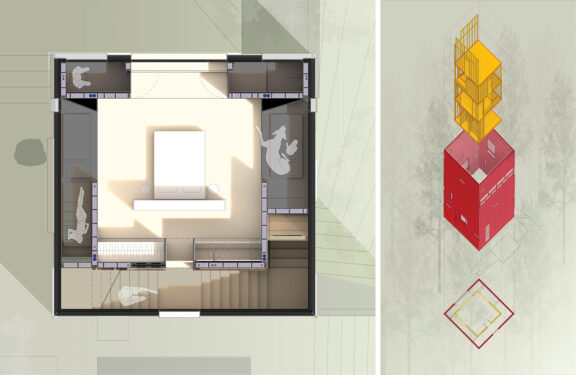

THE RURAL HOUSE/APARTMENT

Located ten minutes from the Shirley train station and less than a three-minute walk from the village center of Ayer, the house embodies a footprint whose relationship to Boston is as proximitous as its connection to the nature of the Nashua River. The idea of a country cabin in the rural landscape is normally thought of as a luxury, and yet we are reminded how the social landscape of our world changed so much in 2020.

The necessity of social distancing, the possibilities of working productively online, and the dynamic nature of the family unit all point to the need for certain new forms of flexibility that only good design can address. In great part, the Rural House/Apartment is a response to this complex array of programmatic possibilities, but it is also a project about overcoming the normative dichotomy between urban and rural living.

SOLID WALL/ HOLLOW WALL: The staircase defines a poché zone of five feet, using the diagonal of the stair to define areas of program below and above its rake. As such, the house is virtually exempt from corridors, as each inch of space is programmed in the thick wall between the central room and the external skin. The exterior wall, outside the stair,

is composed of cross-laminated timber panels, forming a solid load-bearing slab structure are prefabricated off-site. The inner wall beside the stair is conceived of as a traditional stud system—hollow, as it were—to allow space for the infrastructure of the entire house: mechanical, electrical, plumbing systems, and inclusive of acoustic insulation.

FLEXIBILITY: While thought of as a three-room home, the poché spaces offer a wide flexibility, housing anywhere from three to fifteen people without much complexity. Thus, three people could as easily be redefined as three families, three apartments, three Airbnb’s,

or a combination of a host with various rentals, in-law suites, and other combinations that require both integration and autonomy. The living area on the top floor is yet another suite, composed of a long couch and a mezzanine that houses four people on its own.

THE PROMENADE AS PROGRAM: The house is also a typological study of how a single device—a staircase that winds around the periphery of the stacked one-room structure—may bring varied possibilities to the same

structure. Because of the specific arrangement of the stair on each floor, every room offers added space for bunk beds or ancillary bays in which seating can be situated in support of the room.

THE POCHE SPACE: The staircase in the peripheral zone defines a poché zone of five feet, using the diagonal of the stair to define areas of program below and above its rake.

The house is virtually exempt from corridors, as each inch of space is programmed in the thick wall between the room in the core and the external skin, beyond the stair.

The 17th Venice Architecture Biennale “How Will We Live Together?” is curated by Hashim Sarkis.

PROJECT TEAM

Principals: Nader Tehrani, Arthur Chang

Project Coordinator: Alexandru Vilcu

Project Team: Christian Borger, Nicole Sakr, Harry Lowd, Phoebe Cox, Adrian Wong

Printing and Graphics Installation: Arteurbana

Photography by Roland Halbe

Comments Off on La Biennale di Venezia: ‘Other Ways of Living Together’