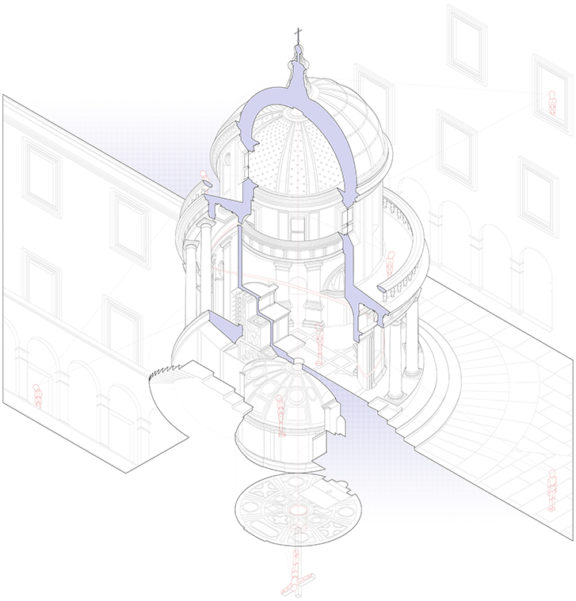

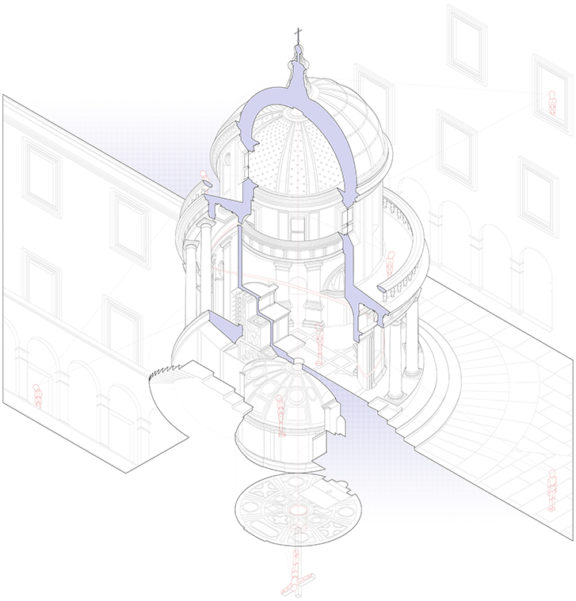

NADAAA contributed a drawing to Tempietto Exemplum, an exhibit at the Yale School of Architecture curated by Amanda Iglesias this Spring. Below is the accompanying text.

See the drawing up close HERE.

St. Peter’s Inverted Crucifixion: Down to Earth, Looking up to the Heavens

Nader Tehrani, 2018

The altar of the Tempietto, located on axis with the entry into the courtyard of San Pietro in Montorio, appears to be composed of monolithic pieces of marble. It is distinct from the conventional altar conceived as a free-standing piece of furniture. Encrypted into the logic of the building’s architecture, the altar is set against the outer wall, further thickening the mass of the load-bearing structure. Consistent with Robin Evans’s article “Perturbed Circles” in The Projective Cast, the position of the altar contributes to the effect of multiple centers achieved in this building, and its de-centering underlines the importance of this choice. Indeed, the altar is not only monolithic, but the inverse. It is composed of a series of thin marble slabs, behind which a cavity allows for a clerestory window into the crypt. The altar serves as the window’s frame, and thus the two are co-dependent.[1]

As partial as it may seem, the sectional detail of this altar reveals something about this building that not only subverts the conventions of its time, but also requires a form of representation beyond the normative techniques of drawing. Due to its curious spatial reciprocity, the figure-ground relationship between the space of the clerestory and the form of the altar is so tight that the building is exempted of the poché characteristic of the structures of this period. If the mass of a traditional wall is meant to provide structural support for a building, it is also the means by which ancillary spaces such as niches and other figural voids can be carved out. The Tempietto does away with this mass altogether, ingeniously conjoining the two functions by using one as the alibi for the other—the altar gives light, and the clerestory offers mass.

This telltale detail of the Tempietto also exposes the difficulty of drawing complex circumstances that require simultaneously looking up and down, if only to show two facets of something inextricably bound together. For this reason, this small structure offers the ideal opportunity with which to advance a form of representation whose purpose is not to illustrate what is already known but to expose the inner workings of something that can only be unearthed forensically. This drawing is the result of the “flip-flop” technique, coined by Daniel Castor in his 1996 book Drawing Berlage’s Exchange, where he demonstrates how this drawing type produces a beguiling form of visual ambiguity that enables the eye to invert the perception of foreground and background.[2] Not dissimilar to El Lissitzky’s Abstract Cabinet 1927 drawing, Castor’s isometric, constructed from a tri-fold 120-degree angle of projection, is distinct in its balanced bias towards the X, Y and Z axes all at once.

The architectural application of this technique resides in the latent alignment between the conventional bird’s eye and worm’s eye views, the latter often attributed to Auguste Choisy. If the bird’s eye view exposes the world of the roof, the worm’s eye reveals the inner workings of the dome, effectively two different symbolic realms. Donato Bramante conceived of both the Tempietto and St. Peter’s Basilica a few years apart, making their conceptual connection somehow inevitable. The Tempietto, a martyrium dedicated to St. Peter, is a folly of sorts—at once a model, a mock-up and a miniature building in its own right with the gravitas of spatial, formal and linguistic tropes that advance the discourse of its time. In its crypt, a pit on center with the oculus, is purported to be the receptacle within which St. Peter’s cross would have been planted upside down, looking up at the dome as it were. In light of the eventual dual-shell construction technique adopted for St. Peter’s dome, one can understand the absolute necessity of looking up and down simultaneously, because the domes are not only symbolically divided but structurally semi-autonomous. By extension, even though the Tempietto is a single-shell structure, the flip-flop technique in this drawing demonstrates the instrumentality of also looking inside and outside simultaneously.

Within the vicissitudes of representational techniques through the centuries, we are beneficiaries of many conceptual advances in the arts that, when seen in tandem, help build a rich repertoire for an analysis of this kind. For instance, Charles de Wailly’s sectional perspectives show the connection between buildings and their urban context in full splendor, in effect bringing the city into the building. The graphic work of M.C. Escher also demonstrates how the latent connections between geometry, space and the construction of perception contribute to their hypnotizing architectural effect. We witness in Picasso’s cubism the desire to overcome the impossibility of seeing many facets at the same time—the front, the back and the sides. In this tradition, as an extension of Castor’s own work, this composite drawing looks up and down, inside and out, toggling back and forth, taking advantage of the isometric’s unique visual sleight of hand to reveal the anomalous alignments, correspondences and reciprocities that would otherwise remain lost in the seemingly pure and idealized form of the Tempietto.

[1] The complex relationship between the building’s oculus, connecting the chapel and crypt, as well as the crypt’s clerestory, diagonally drawing in light from the exterior, is lovingly depicted in Paolo Sorrentino’s 2013 La Grande Bellezza, effectively linking the multiple centers in one shot (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OYwIoxnUWjg),

[2] The Yves Alain Bois essay, ‘Metamorphosis of Axonometry’ makes reference to the Josef Albers painting Structural Constellation, wherein the visual symmetry of the drawing produces simultaneous depth and flatness. Accordingly, as the eye toggles back and forth between the two sides of the drawing, it can be seen to perceptually pop in or out.

CREDITS: Nader Tehrani, Katherine Faulkner, Lisa LaCharité, Mitch Mackowiak

Comments Off on ‘Down to Earth, Looking up to the Heavens’