BY: NADER TEHRANI

AS PUBLISHED TODAY BY ARCHITECT’S NEWSPAPER

In a manner befitting of the current American presidency, Donald Trump’s casual tweet “….we have targeted 52 Iranian sites (representing the 52 American hostages taken by Iran many years ago), some at a very high level & important to Iran & the Iranian culture, and those targets, and Iran itself, WILL BE HIT VERY FAST AND VERY HARD. The USA wants no more threats!” aired some forty-eight hours ago. In fact, the president’s threat does not merit further comment beyond what has been articulated widely in the press: to destroy cultural sites would be an illegal act, and moreover a war crime. Trump’s threat has already been retracted by the Pentagon in what is, by now, a common pattern of contradictory communications so endemic of this administration.

The fifty-two target sites in Iran are claimed to be symbolically linked to the fifty-two American citizens that Iran held hostage in 1979, as if those individuals asked for retribution after forty years. For those of us who remember the hostage crisis and the 444 days of suffering it created, the trauma was real and the political implications have remained intact for over forty years. But for those who remember a generation prior, we are reminded of the infamous 1953 American intervention in Iran that sowed the seeds of systematic mistrust, when a U.S. administration participated in a coup that overthrew a democratically elected Mossadegh to reinstate the Shah’s dictatorship that would guarantee American access to oil. Indeed, the Iranian Revolution may have crested in 1979, but its roots can be linked to an earlier upheaval where the American involvement cannot be understated. As the White House scrambles to justify recent actions, we are wise to recall that the direct U.S. involvement and complicity in the creation and destruction of nations is not restricted to the Iranian experience. Iraq is now reliving its own trauma, the result of rogue American judgment and the coercion of a prior U.S. administration, whose facts were not only flawed but intentions clearly motivated by an a priori decision to occupy a foreign land without any appeal to the truth.

The more significant question that underlies this premise is to what degree the United States can be held accountable in the International Court of Justice in the Hague for its crimes. The United States is not a State Party to the Rome Statute which founded the International Criminal Court. By refusing to participate, the U.S. also sees itself as exempt from the international system that attempts to bring to justice the perpetrators of war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide, when national courts are unable or unwilling to do so. Insofar as the destruction of cultural sites continues to fall under these protective measures of the World Court, then the aim of this piece is also to demonstrate a broader link between cultural heritage, foreign policy, and a system of governance on which we can rely for checks and balances, both national and international. Though not visible at first sight, the environmental policies that drive foreign affairs is also at the center of this narrative, making important links between the American way of life and its reliance of fossil fuels, the very factor that is coming to challenge how we view the environment, whether in cultural or ecological terms.

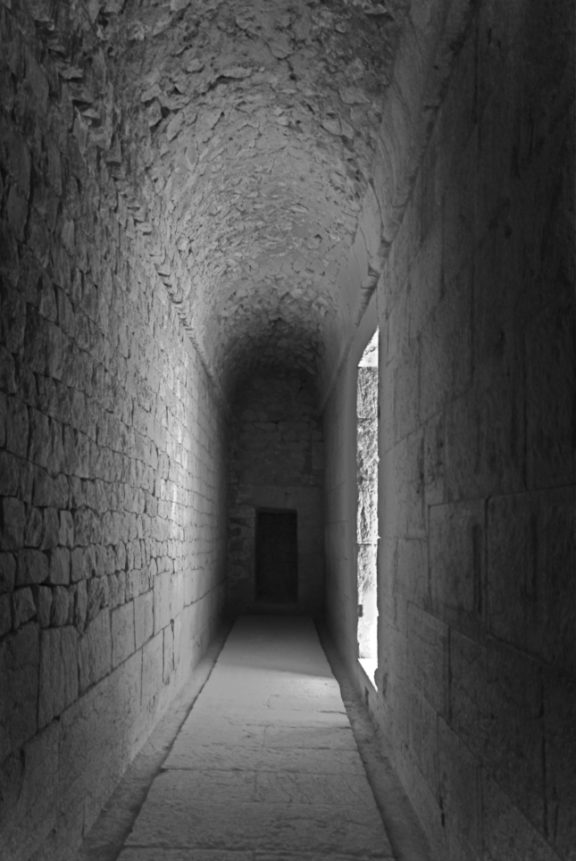

A rudimentary scan through the various heritage sites in Iran unearths a wide variety of cultural significance, protected by both World and National Heritage registers, identifying the very diversity of this region’s history. Indeed, even if the current regime’s theocracy has only enjoyed about forty years of leadership, Iran is composed of many people, tribes, and religions including Zoroastrians, Christians, Jewish, Bahai, and of course Muslims, both Sunni and Shiite. The country’s cities are known for the many contributions they have made to art, science, and architecture, as made apparent through works of infrastructure, urbanism, landscape, architecture, sustainability, and building technologies. The “Qanat” of Gonabad is estimated to be 2700 years old and an early invention of an underground aqueduct, an infrastructural system designed for arid climates –allowing provisions for agriculture, bathing, drinking water, and human survival. In turn, the urban promenade that binds Naqshe Jahan Square, the Bazaar, and the Si-o-se-pol Bridge on the Khaju River in Isfahan forms one of the most significant examples of urban design known to the discipline.

The housing fabric of Kashan and their contained landscapes, “Hayats” and “Baghs”, are the basis for some of the early doctrines of landscape architecture. The wind-catching “Badgir” towers of the Yazd houses are some of the earliest examples of sustainable cooling strategies of this region’s architecture. Of course, beyond public monuments like the well-known Shah and Sheikh Lotfollah Mosques, there are many other classic icons, like the Soltanieh Mosque, whose double-shell dome is one of the most innovative engineering feats of its time, built some one hundred years prior to Brunelleschi’s in Florence. Some of the earlier passages of the region’s heritage go back to Antiquities, and Pasargad, Persepolis, and the cube of Zoroaster take us back to a time when Persia’s international relations formed a completely different dynamic with Greece. Of that era, the Cyrus Cylinder, dating back to the 6th century B.C. remains maybe one of the earliest artifacts to document the idea of a unified state under higher governance with a direct appeal to human rights as part of its contribution to humanity. Thus, while examining the current political predicaments of our moment, it is important to look at this culture’s history, with over 3000 years of documented heritage, to establish how the diversity of its people come to contribute to the legacy of world culture, and indeed, part of its living history.

While few will challenge American generosity in the Second World War and its seminal role in building an alliance that addressed war crimes that defined the 20th Century, the White House’s self-entitlement today is a means to escape the very standards of law and democracy that stoke our national pride and the civil values foundational to American society. Ironically, this sense of entitlement is also foundational to what has allowed the Trump administration to relieve itself of accountability for other questionable actions over the past three years—a factor that prior generations of American leaders could neither have calculated nor fathomed. Sadly, this administration’s hubris is now part of this nation’s ethos; reversing it will be a task to reckon with in the coming years, if not decades, and it will fall on the collective shoulders of the entire nation to address.

As we ponder the American omnipresence in the Middle East, Australia burns with a vengeance, a disaster seemingly unrelated to Iran in both cause and effect. And while it burns, the country’s Prime Minister returns from a family vacation in Hawaii, only after being compelled by mounting political pressure, too little too late. With all the scientific evidence behind the sources of global warming and its impact on climate change, Prime Minister Morrison remains unswerving in his commitment to the investments of fossil fuels, coal and the many policies his party holds dear in its commitment to profit. In this sense, Morrison follows a path no different than that of his American cohorts, whose military presence in Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, among other places in the Middle East has defined American foreign policy for decades. Beyond the social, economic, and cultural upheaval, industry-first policies have produced the injustice of climate inequity, the very phenomenon that stands to compromise not so much humanity (although it will) but the ecosystems, flora, and fauna that do not have the legal instruments to protect themselves. Thus, the American immunity to the World Court is no small issue, because the scale of its ramifications can only be measured in relation to global forces, not merely national ones. It will only be a matter of time when the balance of world economies in Asia take a turn towards other super-powers whose might will define America’s position in the future world order. However, the imposition of their reign may not be paired with the promise of democracy, equity, or a civil society; it is at that junction when we, as Americans, will regret to have abandoned the very values for which we would want to be known today and for history to have recorded for the future. By absolving ourselves of international responsibilities in the World Court today, the US guarantees precedence for others to do the same in the future. Moreover, the current U.S. administration’s abandonment of collaborative dialogue with the United Nations, UNESCO, The Paris Accord and other world bodies only exacerbates the possibilities of other rogue states, whose strategic interests in the future might be to establish their primacy over the greater good of a global community.

Trump’s disregard for democratic institutions, collective processes, and legal frameworks is only radicalized by his penchant to isolate individuals or smaller interest groups as a basis for assault. His current bombast on Iran is no different from what we have witnessed him unleash on African Americans, women, Mexican immigrants, the LBGTQ community, and many others whose diverse backgrounds, belief systems and ways of life differ from his own. Within this context, the destruction of cultural heritage sites can only be interpreted as a targeted attack on the very significance of cultural diversity, and the role that monuments play in the representation of a people.

I am reminded of the vacuous niches that once held the monuments of Bamiyan. Magnificent Buddhas were destroyed in 2001 by the Taliban in an act of brutality, using cultural artifacts as pawns to eviscerate an ‘other’ culture than that of their own. Among other things, the Rome Statute was put in place precisely to protect from such eventualities. Trump’s prejudicial pattern of destruction is perhaps even more sinister because it is inflicted without pause. Some have misperceived Trump’s thuggish mockery of Greta Thunberg—an enlightened embodiment of the next generation—as an assault on an individual. Indeed, it was, but it was also a concurrent assault on the collective: on civil society, on a cultural heritage, on critical discourse, and in the age of Thunberg, on the global environment. Within this context, it is virtually implausible to make a case for the protection of cultural heritage without reinforcing the very foundations on which they rely: A global environment that is sustainable, and a faith in governance and policies of stewardship that can uphold it.

The individual and the collective take on a different resonance in the context of Trump as a person and the system of governance that supports him. It is completely understandable that an individual may not be able to comprehend the basic tenets of fairness, decency or democracy; less digestible is witnessing an entire political party that shuts its eyes to a pattern of behavior that has demonstrated itself to be no accident. There may be no larger strategy to this president’s actions, but there is nothing unpremeditated: Trump behaves the way he does by design. More alarmingly, an entire Republican party behind him, composed of hundreds of individual leaders, support his illegal actions, whether in enunciated defense or silence. Without a restoration of democracy, in the way in which this country’s founders had imagined, it is hard to conceive how its politicians can advance collective agendas that transcend the terms of party lines, and moreover world politics, whose relevance to the United States should be heeded.

The Iranian Revolution occurred in 1979, and its current regime is well-aware of its statute of limitations; with a population of 81 million people –that is, 43 million more than the time of the revolution—the Iranian government understands that its youthful majority can only thrive with a completely different interaction with the international sphere. Despite its acrimony with the West, the achievements of the nuclear deal set in place with the former U.S. administration demonstrated wisdom from both the East and the West. Gain can only come from good communication, collaboration and an appeal to an expanded discursive field. Here, I would argue, the nuclear deal (JCPOA) was not actually the only target, but the means to develop a discussion that could be temporally transported to future administrations: effectively to build better collaborations over time.

Ironically, the Mullahs clearly understood the impending dangers of obsolescence; in order to survive, they could no longer isolate themselves from the world. The current isolationist doctrine of the United States has not only alienated its conventional adversaries; recklessly, but it has also distanced itself from the very allies that hold their connection to America so dear. For America to remain relevant to these audiences, the first step will be to recognize the all-important inter-relationship between global phenomena that sees no borders. Whether considering climate change, economic equity, fair trade policies, or the mutual respect of other’s heritage, an integrated view of world interests might be the only way for securing American priorities in a meaningful way. The monuments that populate seemingly remote regions of the world are not the ‘other’ of America; they are its foundation, its source, and its reference, and once we recognize America’s diversity again, we can also re-enter the global dialogue. An understanding of shared governance may also be the only path towards a strategic plan for survival: there is no America once the global sphere is compromised beyond repair. The disengagement of these relationships can only help to obscure the many causalities that have given rise to the dire state of affairs today.

Comments Off on Cultural sites under attack in the age of unaccountability