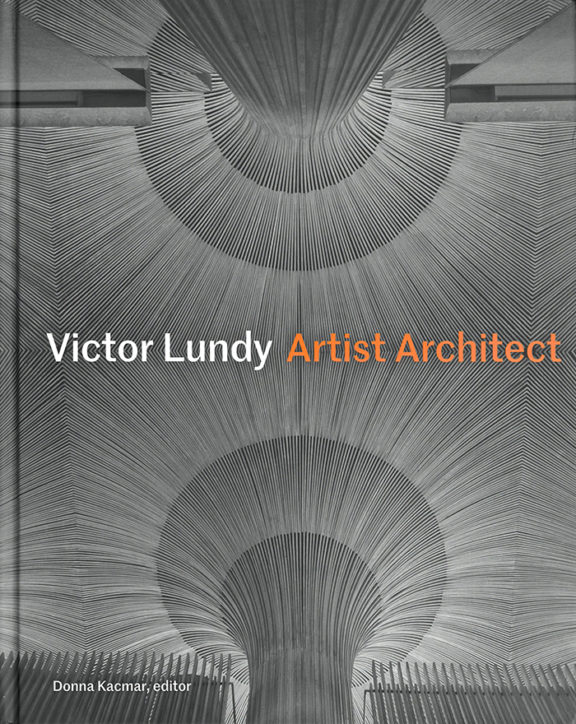

Curated and prepared by Michael Meredith, the ‘Beyond The Harvard Box’ exhibition and Symposium, now a decade old, included a range of critical voices from the Modern era –among them, Edward L. Barnes, John Johansen, I.M. Pei, Ulrich Franzen, Paul Rudolph and Victor Lundy– whose voices were an important part of the evolution of the canons to which they responded.

Watch the full symposium here: Part 1 / Part 2

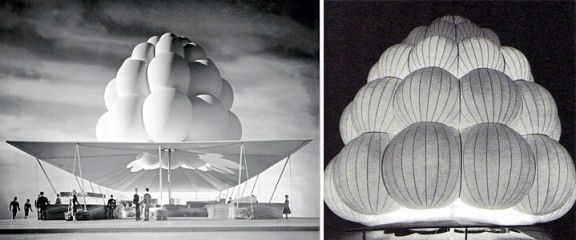

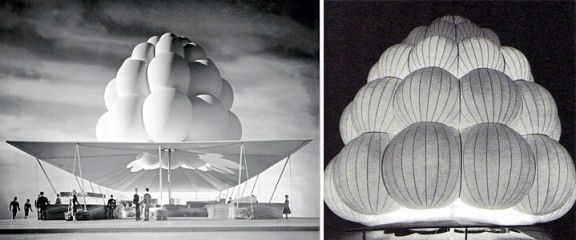

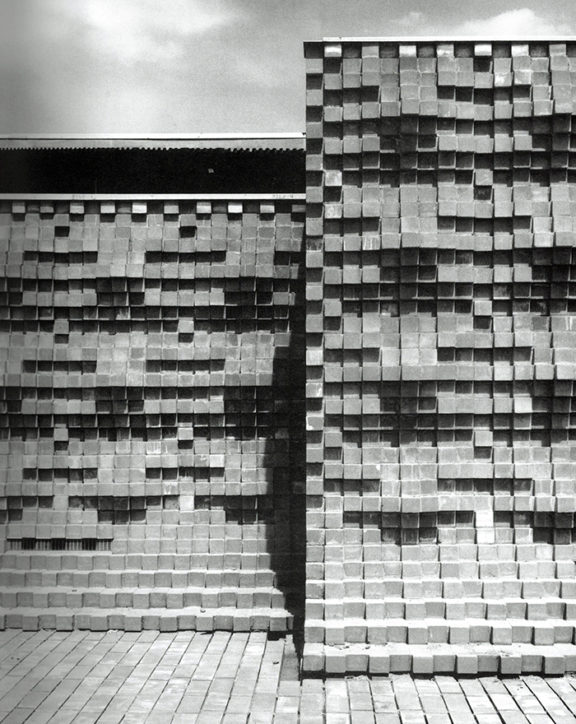

Air Flowers, New York World’s Fair, 1964

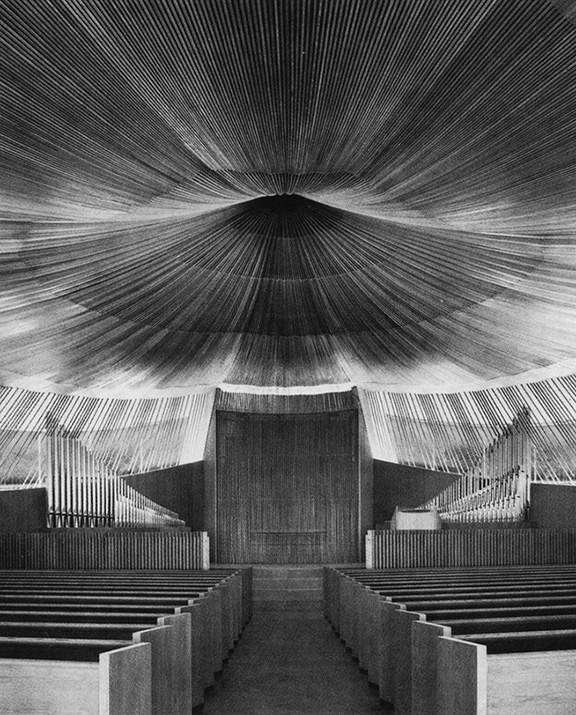

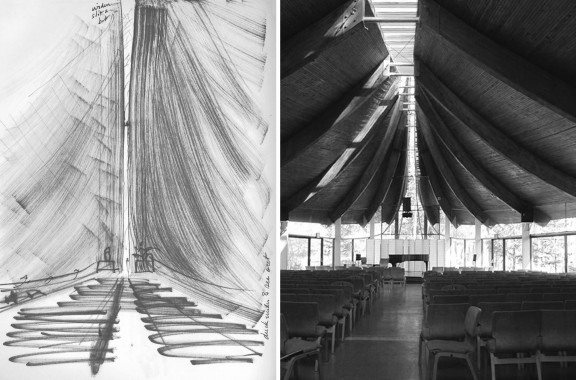

Of them all, Lundy stands out for his persistent attention to material agency: the careful engagement of material technologies as the prerequisite to design. What Lundy’s work demonstrates is the possibility that rules of composition, whether classical or modern, do not necessarily need to preempt design approaches, but rather that the discrete and incremental unit of material organization can become the DNA that enables multiple compositional predispositions. For this reason, even though many of Lundy’s buildings manifest well-known figurative and monumental strategies, they also reveal how material units offer many alternative formal, spatial and organizational potentials.

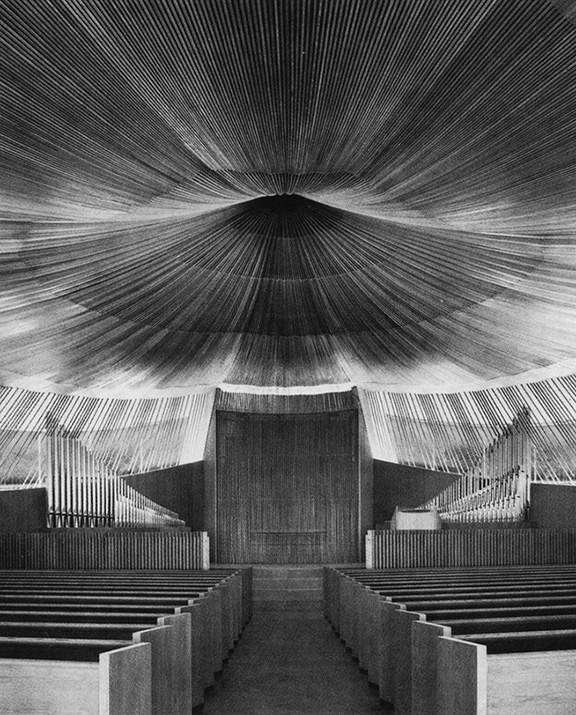

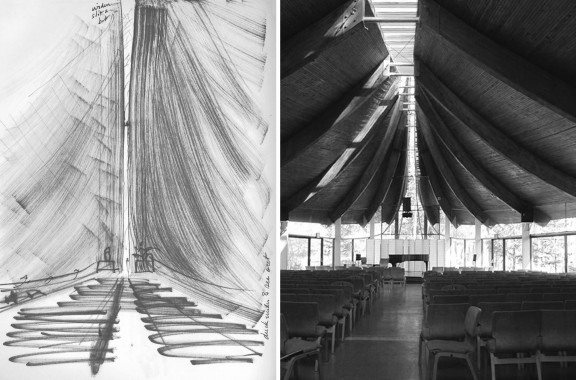

Unitarian Meeting House, Hartford, Connecticut, 1964

Canopies, Museum of History and Technology, now known as the National Museum of American History, c. 1967

The work itself is also characterized by an authorship that denies signature in the form of a common style or singular voice; instead each project achieves a material sensibility that emerges from operations on material behavior, methods of aggregation, and their requisite formal malleability. As such, its part to whole relationships enjoy the same precision as Mies Van der Rohe’s work, but its formal and figurative ambitions are more aligned with the type of exploration that Le Corbusier might have entertained. At the same time Lundy’s materiality suggests a texture and density that only Aalto would have engaged, but in Lundy’s hands it is much more intellectually targeted and materially restrained. These composite characteristics make Lundy less prone to easy characterization and, in turn, less consumable. In great part, this is why he did not reach the pantheon of the great modernist architects or achieve a wider audience, but if seen from the viewpoint presented here, he exemplifies a paradigmatic position that in hindsight has become a classic.

First Unitarian Church, Westport, CT, 1960

From the perspective of our own research, the connections are obvious, but one can extend this lineage to protagonists like Herzog & de Meuron before us who realigned thinking in relation to materials— to a younger generation of architects after us, like Skylar Tibbits who have been rethinking material behavior at the molecular level. Looking back at the video of the Symposium, what is startling, and humorous, is my desperate attempt to draw out this thesis from Lundy himself, alas to futility. His intellectual project is implicit, even in those moments when he refutes them, or so I hope, as they emerge from the precise constructive composition of the work itself.

IBM Garden State Office, Cranford, NJ, 1965

Comments Off on Reflecting on Victor Lundy and ‘Beyond the Harvard Box’

image above: IBM Garden State Office Building, Cranford, New Jersey, ,1964 / cover image: I. Miller Showroom, Grand Hall, New York City, 1962

image above: IBM Garden State Office Building, Cranford, New Jersey, ,1964 / cover image: I. Miller Showroom, Grand Hall, New York City, 1962